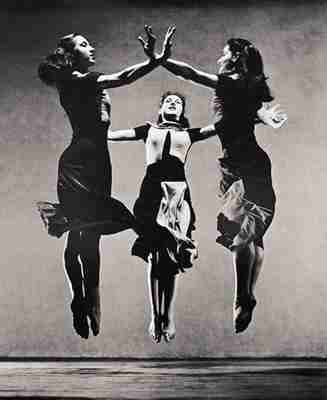

An Unforgettable Photo of Martha Graham

Barbara Morgan’s 1940 image of Martha Graham in the ballet Letter to the World may be the most famous photograph ever taken of an American dancer. It ranks, in honor, with Ansel Adams’ photographs of Yosemite and Walker Evans’ of small-town churches, and it bears much the same message: Americans’ belief in the flinty, frank truth of their vision of life, as opposed, say, to European decorativeness and indirection. That faith was especially strong around the mid-20th century, and in the minds of certain artists it was allied especially with the American Southwest: the hogans, the cliff-hemmed mesas, the vaulted skies. D.H. Lawrence and (the best-known example) Georgia O’Keeffe lived there. Many others traveled there, including the California photographer Barbara Morgan.

Born in 1900, Morgan worked in several media—printmaking, drawing, watercolor—but by the mid-’30s she was concentrating on photography, partly because it was easier to do with two children in the house. In the summers, she and her husband, Willard, a writer and photographer (he would be the first director of photography at New York City’s Museum of Modern Art), visited the Southwest and turned their cameras on the landscape. Another devotee of that part of the country was the dancer and choreographer Martha Graham. Graham, born in 1894, first visited the Southwest in 1930. The place hit her like a brick, and confirmed her quest for an austere and ritualistic style.

Thus when Graham and Morgan met, in 1935, they found they had a shared interest. Indeed, they had much in common. Both were dedicated modernists and hence, at that time in America, bohemians, iconoclasts. In addition, both were highly idealistic, given to pronouncements on the Spirit, the Essence and so forth. According to the philosopher Curtis Carter, a friend of Morgan’s who has curated three exhibitions of her work and written most of what we know about her, Morgan had first seen Graham’s work several years earlier. We don’t know if Graham had seen Morgan’s work, but apparently she sensed a kinship. Within a short time Morgan proposed to do a book of photographs of Graham, and the choreographer said, “Fine, let’s do it.”

It was not an easy project. “She was a terror,” Graham told an interviewer years later. “I’d do it, and then she’d say, ‘Well, the dress wasn’t quite right,’ and then we’d have to do it again. First she would make me lie down on the floor and rest. So off came the dress (it mustn’t get dirty, you know), and then we’d start all over again.” Morgan had her reasons—exalted ones, as usual: “I wanted to show that Martha had her own vision,” she said about the photo shoots. “That what she was conveying was deeper than ego, deeper than baloney. Dance has to go beyond theater....I was trying to connect her spirit with the viewer—to show pictures of spiritual energy.” Graham probably agreed. In the book Morgan finally produced in 1941, Martha Graham: Sixteen Dances in Photographs —which contained the Letter to the World image—Graham writes, “Every true dancer has a peculiar arrest of movement, an intensity which animates his whole being. It may be called Spirit, or Dramatic Intensity, or Imagination.”

Nowadays, these words sound a little high-flown, as do many writings of the period (think of Eugene O’Neill or Tennessee Williams), but the combined ardor of Graham and Morgan produced what—with maybe one competitor, George Platt Lynes’ images of George Balanchine’s early work—were the greatest dance photographs ever made in America. Morgan thought she was just celebrating Graham. In fact, she was celebrating dance, an art often condescended to. The composition of the photograph is beautiful—the horizontal line of the torso echoing that of the floor, the arc of the kick answering the bend of the arm to the forehead—but this is more than a composition. It is a story. Letter to the World is about Emily Dickinson, who spent her life shut up in her family’s house in Amherst and who nevertheless, on the evidence of her poetry, experienced in those confines every important emotion known to humankind. Graham’s dance was accompanied by readings from Dickinson, including:

Of Course—I prayed— And did God Care? He cared as much as on the Air A bird—had stamped her foot— And cried “Give me!”—

Unanswered prayers: most people know what that means. Hence the seismic power of the photograph.

Both Morgan and Graham lived to be very old, Morgan to 92, Graham to 96. Graham became this country’s most revered homegrown choreographer. She, more than anyone else, is now considered the creator of American modern dance. Twenty years after her death, her company is still performing. Morgan’s reputation remained more within the photographic and dance communities. By the late 1970s, her book was out of print (old copies were selling for $500) and it was often stolen from libraries. But it was reprinted in 1980.

Joan Acocella is the dance critic for the New Yorker .

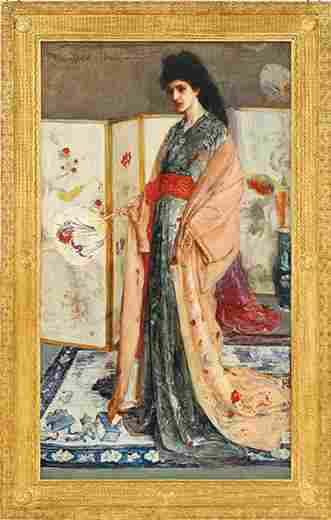

The Story Behind the Peacock Room’s Princess

The great American expatriate painter James McNeill Whistler is best known, of course, for his Arrangement in Grey and Black , a.k.a. Whistler’s Mother , an austere portrait of a severe woman in a straight-backed chair. But judging Whistler only by this dour picture (of a mother said to have been censorious toward her libertine son) is misleading; the artist delighted in color. One painting that exemplifies Whistler’s vivid palette, The Princess from the Land of Porcelain , constitutes the centerpiece of the Peacock Room at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art.

The work was owned by English shipping magnate Frederick R. Leyland in 1876 and held pride of place in the dining room of his London house, where he displayed an extensive collection of Chinese porcelain—hence the painting’s title. The subject was Christina Spartali, an Anglo-Greek beauty whom all the artists of the day were clamoring to paint. In 1920 the Smithsonian acquired the painting and the room (essentially a series of decorated panels and lattice-work shelving attached to a substructure). A new Freer exhibition, “The Peacock Room Comes to America,” celebrates its splendors through April 2013.

The Princess is also featured on the Google Art Project ( googleartprojecom ), a site that employs Google’s street-view and gigapixel technologies to create an ever-expanding digital survey of the world’s masterpieces. The average resolution for displayed works is seven billion pixels—1,000 times that of the average digital camera. This allows Internet users to inspect works up close, as if with a magnifying glass held just inches from a priceless painting.“Gigapixel reproduction is a real game changer,” says Julian Raby, director of the Freer and Sackler Galleries, making a Web view of a painting “an emotional experience.”

The Peacock Room (named for the birds Whistler painted on its shutters and walls) reflects the tension between the artist and his first significant patron. Leyland had hired Thomas Jeckyll, a prominent architect, to design a display space for his mostly blue and white Qing dynasty (1644-1911) porcelain collection. Because The Princess was hung over the fireplace, Jeckyll consulted Whistler about the room’s color scheme. While Leyland headed back to Liverpool on business, Jeckyll, having health problems, stopped overseeing the work. Whistler, however, pressed on, adding many design details, including the peacocks on the shutters.

In a letter to Leyland, Whistler promised “a gorgeous surprise.” Leyland was surprised all right, by embellishments far more extensive and expensive—some 2,000 guineas (about $200,000 today)—than he had anticipated. “I do not think you should have involved me in such a large expenditure without previously telling me of it,” he admonished Whistler.

After Leyland agreed to pay only half, Whistler did some more work on the room. He painted two more peacocks on the wall opposite The Princess . The birds faced each other, on ground strewn with silver shillings, as if about to fight. Whistler titled the mural Art and Money; or, the Story of the Room . Then Whistler painted an expensive leather wall covering with a coat of shimmering Prussian blue, an act of what might be called creative destruction. According to Lee Glazer, curator of American art, after Whistler finished in 1877, Leyland told him he would be horse-whipped if he appeared at the house again. But Leyland kept Whistler’s work.

Leyland died in 1892. A few years later, Charles Lang Freer, a railroad-car manufacturer and Whistler collector who had earlier bought The Princess , acquired the Peacock Room. He installed it in his Detroit mansion as a setting for his own extensive collection of Asian pottery and stoneware. He bequeathed his Whistler collection, including the Peacock Room, to the Smithsonian in 1906, 13 years before his death. For the new exhibition, curators have arranged the room as it looked after coming to America, with the kind of pottery and celadon pieces that Freer collected and displayed, instead of the blue and white porcelain favored by Leyland.

Whistler’s sophisticated color scheme presented challenges even to Google Art’s state-of-the-art technology. “The shadows and subtle colors proved a huge problem for the camera,” says Glazer. “I can’t help but think that Whistler would have been pleased.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions .

Law and Order: Jell-O Gelatin Unit

Our concept of Jell-O-centric criminality typically doesn’t go beyond the idea of ill-conceived potluck salads with fruits or vegetables suspended in the death grip of technicolor molded gelatin. (We all smile and politely eat them anyway.) But while researching a recent post on Jell-O , I came across several instances of the jiggly dessert being at the root of some nefarious activity. I’ve enjoyed food and true crime stories —involving files baked into cakes and ice cream men —so much that the following stories were impossible to pass up. Although this is hardly how Jell-O manufacturers want their product to be remembered. “It is not a usage that we promote for Jell-O,” a General Foods spokeswoman said about Jell-O during the Martin Eisen trial (detailed below), “and, as with any product, it has to be used responsibly, and that is the responsibility of the consumer.” From drunk driving to acts of Cold War espionage, here’s a look at how Jell-O has sprung up in our criminal justice system.

New York City, New York. July, 1950. Jell-O and spy rings.

Husband and wife Julius and Ethel Rosenberg were brought to trial in one of the most famous and controversial Cold War-era court cases . They were accused of securing top-secret information about the atomic bomb for the Soviet Union—and a Jell-O box played a role in their conviction. The Rosenbergs orchestrated a meeting between Harry Gold , a New York chemist who was also part of the Rosenbergs’ spy network, and David Greenglass, Ethel’s brother who had worked on the Manhattan Project and had top-secret information on the atom bomb. So that the pair could covertly signal to each other that they were a part of the same spy ring, a Jell-O box was cut up, half of it given to Gold, the other half given to Greenglass. When the two met up, the matching box piece was an “all clear” sign for Greenberg to pass on his bomb information, which eventually made its way back to the Soviet Union. Although the original Jell-O box was never found, a facsimile (a box of raspberry-flavored gelatin, now in the National Archives ) was used in the trial to link the Rosenbergs to the atomic information leak. Greenglass got 15 years in prison in exchange for his testimony against the Rosenbergs while Harry Gold was sentenced to 30 years. Julius and Ethel were convicted on espionage charges and sentenced to death, and both went to the electric chair on June 19, 1953. Whether the punishment suited the couple’s activities later became a hot debate topic. In 2008, Morton Sobell, who was charged with espionage along with the Rosenbergs but had always maintained his innocence, confirmed that he and Julius were indeed active Soviet agents .

Westport, Massachusetts. January, 1990. Death by Jell-O

Richard Alfredo died at age 61 from a massive heart attack, and because he suffered from chronic heart ailments, his mortal end did not come as a surprise. However, police suspected that he did not die from natural causes and an autopsy revealed that he had massive amounts of the hallucinogenic drug LSD in his system. Attention turned to his 39-year-old live-in girlfriend Christina Martin, who moved to Montreal a month after her boyfriend’s passing, and she was put on trial for murder. Witness testimony revealed that Alfredo suffered the heart attack after Martin, thinking she could inherit her boyfriend’s money and property, served him a lime Jell-O dessert that was laced with a lethal dose of LSD. Martin was convicted of the crime in 1992 and sentenced to life in prison.

Los Angeles, California. November, 1992. The Jell-O Defense.

On the evening of November 11, 1992, Martin Barry Eisen was pulled over by police for driving 55 m.p.h. in a 35 m.p.h. zone, and at the time of his arrest, he had a blood alcohol content of .10. At trial, Eisen testified that some 25 minutes before getting behind the wheel, he enjoyed several bowls of cherry Jell-O that, unbeknownst to him, his friend had spiked with vodka . The court failed to sympathize with that line of defense. Eisen was fined $1,053 and ordered to attend 3 months of alcohol education classes.

Durham, New Hampshire. February, 1992. There’s always room for free speech.

University of New Hampshire English professor J. Donald Silva was giving a lecture to his technical writing class and his description of belly dancer Little Egypt’s skills landed the 59-year-old tenured teacher in hot water . “Belly dancing,” he said, “is like Jell-O on a plate, with a vibrator under the plate.” Nine students complained and the university suspended Silva on sexual harassment grounds. Silva later filed suit and in 1994, Federal District Courts ruled that the university violated his first amendment rights and that there were legitimate, pedagogical reasons for his language choices. Silva was reinstated, but the court decision did not address the $42,000 in damages or back pay he had sought.

East Northport, New York. March, 2010. The proof is in the pudding. (Or lack thereof.)

Something was definitely amiss when a Long Island supermarket customer bought a box of Jell-O pudding only to find that it was filled with sand and salt . Police were able to trace the suspicious box back to a Long Island couple, 68-year-old Alexander Clements and his wife of 40 years, Christine, age 64. The couple had a penchant for pistachio and butterscotch pudding and, hitting up four area stores, would buy up to 10 boxes of pudding, take them home to empty their contents and replace the powdered pudding mix with plastic bags full of salt and sand and return the resealed boxes to the store to get a refund. Per the authorities, Christine was suffering from age-related mental issues and the couple did not intend to harm other people—but rather just wanted pudding without paying for it in spite of being financially stable. The couple was arrested and charged with petit larceny and tampering with a consumer product.

Post a Comment