Buried Treasure

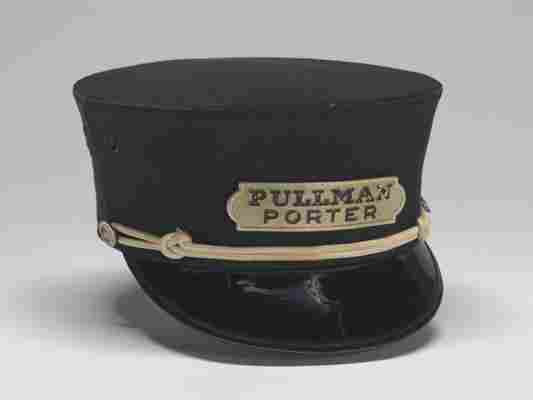

Superficially, it was a hat: worn, discolored, mundane. It once belonged to a Pullman Company sleeping-car porter, an African-American man—the headpiece to a pristine white uniform. Patricia Heaston got it from a friend, whose father was a porter, more than 30 years ago. Heaston, a clinical psychologist, obsessively collected such keepsakes for decades to better understand how black children develop their self-image. This past January, she brought the porter's hat to the National Museum of African American History and Culture's inaugural collections initiative, held at the Chicago Public Library.

The presentation of the cap inspired an excited, impromptu explanation of the occupation's impact on African-Americans. "The story of the Pullman car porters is the key to many things," said Jacquelyn Serwer, the museum's chief curator. It's a story that begins with social mobility; in the 1920s, when the Pullman Company was the largest employer of African-American men in the country, the occupation represented a relatively high-paying, respectable job—albeit one with inequities. The porters had to pay for their own meals and uniforms, which in 1925 led to the formation of the first African-American labor union, the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters. The train attendants were instrumental in other ways. "They could bring back stories to give people a sense of the bigger world available to them," Serwer said. "And because they provided the information that stimulated people to make the move from the South to the North, they were important to the Great Migration."

"In some ways, the little object allows us to tell the great story," said Lonnie Bunch, the museum's founding director. To find such things, he created "Save Our African American Treasures," an enterprising call for families nationwide to ransack attics and basements for historical heirlooms. The initiative has two goals: raising awareness that everyday items gathering dust in people's homes could be crucial to telling the story of African-Americans to future generations; and teaching basic preservation techniques. The museum is planning similar events in Atlanta, Los Angeles, New York City and Washington, D.C.

In Chicago, more than 150 people brought myriad mementos (quilts, Bibles, irons, bank documents and dolls) for Smithsonian conservators to review. Most of the items returned home, but a few will be considered for exhibits at the museum when it opens in 2015.

At the event, an attempt at delicateness quickly gave way to excitement as Bunch removed the Pullman porter's hat from the acid-free tissue paper in which a senior Smithsonian textiles conservator had wrapped it. It was a white hat, a particularly significant commodity, which meant that its owner had tended to prominent guests (perhaps even presidents) on a private train car. "This is the treasure of treasures," Bunch told Heaston, before asking whether she'd consider donating it to the museum. She proved an easy sell: "I'm not going to [unwrap it] until it goes to Washington," she said afterward.

Mark Catesby’s New World

It is no secret that the 18th-century British natural history artist Mark Catesby occasionally copied the work of his predecessors. His sketch of a land crab bears a striking resemblance to a watercolor rendered by John White (see "Brave New World" in the December SMITHSONIAN), a British artist who joined Sir Walter Raleigh's voyages to present-day North Carolina in the 1580s. The crustacean's spiny legs are bent at all the same angles as they are in White's version.

In total, Catesby replicated, possibly even traced, about seven of White's published watercolors. The patchwork of amorphous spots on his puffer fish is virtually identical to White's, and he acknowledges White as the source for his stunning illustration of a tiger swallowtail butterfly. The borrowing of images was quite common at the time. Naturalists viewed their collected works as encyclopedias and were willing to include entries originally authored by others for the sake of being comprehensive. In Catesby's case, scholars suspect that he copied others' illustrations in the rare instances when he hadn't observed the creature on his own or hadn't been in the position to sketch it.

"As an empiricist, Catesby believed that drawings by other naturalists offered him direct access to their own first-hand observations of the natural world," explains Amy Meyers, a Catesby scholar and the director of the Yale Center for British Art in New Haven, Connecticut.

Copies aside, Catesby was innovative in the way he presented his comprehensive survey of the flora and fauna of America's colonies in his Natural History of Carolina, Florida, and the Bahama Islands . While most of his predecessors' illustrations were of birds mounted on dead stumps or ducks bobbing on a shallow strip of water, Catesby's, mostly drawn from life, were some of the first to depict environmental relationships—a bead snake wrapped around the potato root that it's often dug up with or a blue jay shown with the berries it eats.

When Catesby translated his copied drawing of White's land crab into an etching, he added a small branch bearing a dangling fruit, clasped in the crab's claws. In doing so, Catesby created "a study of organic interaction," writes Meyers. "The naturalist thus transformed a traditional specimen drawing into a composition reflecting his own observations of the way in which two species interrelate in their shared habitat." In some cases, however, which Meyers points out are "the exception rather than the rule," Catesby pictured a plant and animal together purely for aesthetic reasons.

Many natural history artists before him drew from specimens carried back to Europe by sailors and diplomats who could only provide the country or region of their origin. But Catesby's etchings often provided information about what an animal feeds on or what plants and animals are found in the same environs—information he could only have attained by immersing himself in his subjects' habitats. Catesby was 29 when he made his first trip to the American colonies in 1712. He stayed with his sister, who was living in Williamsburg, Virginia. Not much is known about his training as a naturalist or artist. Some suspect that British naturalist John Ray and Ray's colleague, botanist Samuel Dale, who Catesby would have known through family connections, may have mentored him. But he explored the Virginia landscape, unsponsored and largely on his own, collecting leaves and seeds and sketching his findings as he followed rivers from settlements to the wilder woods around their sources. After seven years, he returned to England, where members of the Royal Society of London had begun to take interest in his drawings. One member offered him a salary "to Observe the Rarities of the Country for the uses and purposes of the Society," and in 1722 Catesby traveled to Carolina. In the four years he spent there and in Florida and the Bahamas, he combed the fields, forests, swamps and shores for wildlife. He painted watercolors in the field; recorded details such as an animal's coloring, where it was seen and any additional information natives provided; and shipped specimens back to his Royal Society patrons, who often planted his exotic seeds in their gardens.

Soon after returning to London in 1726, Catesby etched his drawings onto copper plates, often combining two different sketches into one to create his engaging and informative compositions. He organized the 220 etchings into two volumes—the first featured birds and plants and the second included fish, insects, reptiles, amphibians, mammals, and the plants associated with them—and decided he would release them in 20-plate installments. With subscribers, many from the upper echelon of society, wanting some 180 copies, he had to hand color close to 40,000 prints. The endeavor amounted to nearly 20 years of labor and literally became his life's work. Catesby died, in 1749, just two years after its completion.

I recently visited the Smithsonian Institution's Cullman Library, a temperature- and humidity-controlled room in the bowels of the National Museum of Natural History that contains two of the estimated 80 to 90 remaining original copies of Catesby's Natural History . Leslie Overstreet, the library's curator of natural-history rare books, pulled from the shelves a classic encyclopedia of animals from the 1560s, a book of John White's watercolors, a major anthology of birds by Catesby's contemporaries and, of course, Catesby's Natural History . Thumbing through the books, I could see the progression from isolated specimens on sterile white backdrops to animals artistically framed by their natural settings. I became acutely aware of the vitality in Catesby's etchings—a blue jay's beak open in mid-song, a viper hissing, a playful lizard hanging from a stalk of sweet gum, a kingfisher slurping down a fish—and I was not surprised when Overstreet said, "It was the book for about a hundred years."

After all, Cromwell Mortimer, secretary of the Royal Society and former owner of one of the Smithsonian's copies, hailed it as "the most magnificent work I know since the Art of printing has been discovered." Carolus Linnaeus named Catesby's trillium, Catesby's lily and Catesby's pitcher plant, as well as Rana catesbeiana , the North American bullfrog, in the naturalist's honor. Not to mention, artist John James Audubon's paintings, done more than a century later, were a natural extension of Catesby's illustrations.

Audubon eventually became the more remembered of the two wildlife artists, but in the last decade, there's been something of a Catesby revival. His appeal has broadened among academics, for one. Overstreet says that the researchers who visit the library to see Catesby's Natural History are split almost evenly between those studying it for its scientific value and those studying it for its artistic value. And there has been a push to increase public awareness of the artist. In 1997, 50 of Catesby's original watercolors, previously owned by King George III, toured America for the first time. This past summer, the Smithsonian Institution Libraries hosted "Mark Catesby's America," a symposium featuring experts who approached the artist and his work from the perspectives of science, art and history. The 2007 documentary "The Curious Mister Catesby" was shown at the symposium and now its producers will be encouraging public television networks to air it on Earth Day in April. An exhibition titled "Catesby, Audubon, and the Discovery of a New World" opens December 18 at the Milwaukee Art Museum. And following the example of a few other institutions, Smithsonian Libraries will be creating a digital copy of Natural History for inclusion on an all-Catesby Web site to be launched next year.

Adding an element of poignancy to Catesby's story is the fact that several of the species he depicted (the parrot of Carolina, the largest white-billed woodpecker and the greater prairie chicken) are now extinct and others (the hooping crane, flying squirrel and wood pelican) are endangered.

"We must look closely at how well 18th-century Colonial naturalists in the trans-Atlantic world understood that the project of empire was setting into motion new patterns of organic interaction, since it involved not only the movement of people, but other living organisms from across the globe," says Catesby scholar Meyers. "Catesby understood that radically new organic relationships were being established that would remake this New World in highly significant ways."

Surely there's a lesson to be learned in his passion.

“No More Long Faces”

Gawking at the love lives of public figures–from Brangelina to Eliot Spitzer–is something of a national pastime these days, and things weren't much different during the lifetime of celebrated American artist Winslow Homer (1836-1910).

While prolific in depicting the outside world, Homer adamantly refused to reveal his inner landscape to an increasingly curious public throughout his career. Perhaps that is why, nearly a century after his death, we're still interested: Secrecy often suggests something worth concealing.

Homer himself hinted at this sentiment in a 1908 note to a would-be biographer: "I think that it would probably kill me to have such a thing appear–and as the most interesting part of my life is of no concern to the public I must decline to give you any particulars in regard to it."

Although Homer remained a bachelor for all of his 74 years, after his death, one of his close friends told biographer Lloyd Goodrich that the artist "had the usual number of love affairs." No conclusive evidence is available about any of these, but a thin trail of emotional clues exists amid Homer's correspondence with friends and family, as well as in his work.

The first such clue comes in a March 1862 letter to his father, Charles Savage Homer. The young Homer is planning to travel to Washington to illustrate Civil War action for Harper's Weekly , and mentions a comment made by his editor: "He thinks (I am) smart and will do well if (I) meet no pretty girls down there, which he thinks I have a weakness for."

Homer spent ten months in France in 1866-7, and had an active social life there, if his vivacious engravings of Parisian dance halls are any indication (see above sketch). For the next five or six years, back in America, he continued to paint generally cheerful, lively scenes, often featuring pretty young women.

"The numerous portrayals of fetching women suggest a longing for feminine company…these scenes may have been this shy man's way of safely bringing women closer," Randall Griffin wrote in his 2006 book Winslow Homer: An American Vision .

Specifically, it seems the painter yearned to be closer to Helena De Kay, an art student and the sister of Homer's friend Charles De Kay. She was the apparent model for several of Homer's works in the early 1870s, until she married the poet and editor Richard Watson Gilder in 1874.

As fine arts scholar Sarah Burns explained in a 2002 article for The Magazine ANTIQUES , Helena De Kay's correspondence shows how Homer may have tried to court her. Homer often asked her to visit his studio, an invitation he rarely extended to anyone, and she is the only painter he ever offered to instruct (though there is no evidence she accepted). In one note, he even compared a photo of her to a Beethoven symphony, "as any remembrance of you will always be."

Perhaps Homer's circa 1872 oil "Portrait of Helena De Kay" reflects his realization that he would likely lose his beloved to Gilder, who began courting her that year. It was an unusual work for Homer's style up to then – a somber, formal portrait, and an uncommissioned one at that.

In the painting, DeKay is seated on a couch in profile, dressed in black and looking down at a closed book in her hands. The indoor setting, presumably Homer's studio, is dark and empty but for a small spot of color on the floor–a discarded and dying rose; a few of its petals scattered nearby.

It is "a very suggestive picture, and unlike any other he painted," says Nicolai Cikovsky Jr., a Homer biographer and retired National Gallery of Art curator. "I'd say she is the most nameable candidate (for a love interest), certainly."

A letter from Homer to De Kay in December 1872 indicates that something had come between them. He asks her to pick up a sketch he had made of her, adding a few cryptic words of reassurance: "I am very jolly, no more long faces. It is not all wrong."

The next year, another of Homer's notes alludes to his feelings by what it omits: "My dear Miss Helena, I have just found your picture. I think it very fine. As a picture I mean, not because, etc."

It is unclear whether Homer ever actually proposed to De Kay, but he painted a picture of a proposal scene in 1872, with the telling title, "Waiting For an Answer," and in 1874 he painted an almost identical scene minus the young suitor ("Girl in an Orchard"), suggesting that the girl's answer had been to send the boy away. Around the same time, he painted several other pictures of "thwarted love," as Burns describes it.

Some scholars think he fell in love again a few years later, when he was around 40 years old. He visited friends in rural Orange County, New York, and painted several pictures of women there. One of them, titled "Shall I Tell Your Fortune?" shows a saucy-looking lass seated barefoot on the grass, holding playing cards in one hand. Her other hand rests palm-up on her hip, and her direct gaze seems to be asking the painter much more than the title suggests.

A similar woman appears in other Homer paintings from the mid to late 1870s, and this may have been the schoolteacher referred to by Homer's grandniece, Lois Homer Graham, in a piece she wrote for the book Prout's Neck Observed decades later: "The year 1874 found all of the Homer sons well established in their careers…Winslow had courted a pretty school teacher, but lost her to his career."

It does seem clear that Homer wanted a major change of scenery and lifestyle rather suddenly at the end of the 1870s. As Cikovsky puts it, "something was stirring in Homer's life, and I think some sort of intimacy gone wrong was part of that."

The artist withdrew from society, moving first to an island off Gloucester, Mass., then the remote fishing village of Cullercoats, England, and finally in 1883 to Prout's Neck, Maine, where he stayed the rest of his life. He developed a reputation as a grumpy recluse, discouraging visitors and turning down most social invitations, although he remained close to his family. His personal life may have suffered, but his professional life flourished in these years, as the seacoast inspired some of his best works.

Interestingly, Homer never attempted to sell the painting of the fortune-telling girl. It was still on an easel in his Prout's Neck studio when he died in 1910.

But before you get too wrapped up in the romance of that idea, keep in mind that alternate theories abound. Homer scholar Philip Beam thinks the mystery woman was no woman at all, but rather a boy modeling as a woman for the "girl-shy" painter.

At least one reviewer has argued that Homer was homosexual, though most art historians now reject the theory. Others, including Beam, think he was simply married to his work.

"To an artist of Homer's caliber much is given, but if he is to put his great gift to its fullest use, much is also demanded. So much that there is little time left to share with a wife," Beam wrote in Winslow Homer at Prout's Neck (1966).

The truth, it seems, remains as stubbornly elusive as the artist himself.

Post a Comment