Dark Doubling

Gregor Schneider works in peculiar ways. A German sculptor and installation artist, he came on the scene in the mid-1980s for spending almost a decade dismantling, recreating and exhibiting, down to the slightest detail, the rooms in his home. The mere reconstruction is a fairly prosaic exercise, but the attentive focus on recapturing every last cracked ceiling tile, stained carpet or water stain, comes off as a perverse compulsion and taints the viewer’s visit with unease; very likely the artist’s intention.

In a similar response to architecture, Schneider used white or "clean" torture (interrogation tactics that leave no physical mark on victims) and images of the U.S. prison at Guantanamo Bay as inspiration for building interrogation rooms or holding cells, and inserting these environments into a museum context.

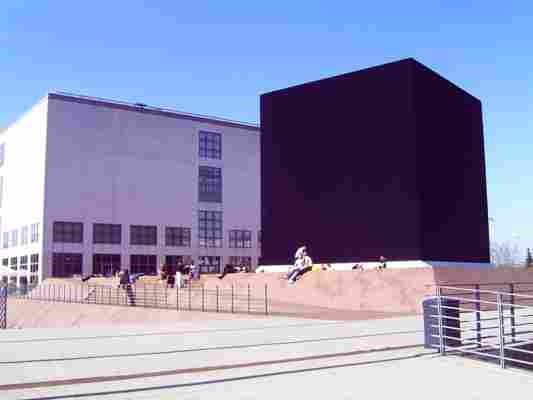

The artist is also known for "Cube Venice," his contribution to the 2005 Venice Biennale in the form of a 50-ft.-sq. scaffolding, draped in black and erected in the middle of touristy San Marco square—a play on the Ka’aba in Mecca.

Schneider’s sculptures also evoke psychological anxiety. "Mann mit Schwanz" (Man with Cock) (2004) is a prime example. The top half of a plaster cast of a man’s body is swathed in a black trash bag, obscuring identity or expression. The lower half of the body is dressed in sweat pants and fitted with an erection. Perversion and death are inextricably intertwined, as the viewer is not sure if this is a disturbing murder scene or sexual tableau.

All that being said, it is still startling to hear that most recently Schneider announced his plans for a performance piece that includes a person dying or the body of someone who is recently deceased. He aims “to show the beauty of death" as quoted in The Art Newspaper. Schneider has teamed up with a physician who is apparently willing to help him find volunteers who think art is worth dying for.

Gettysburg Address Displayed at Smithsonian

In American History, November 19, 1863, might be considered a day of wind and fire.

The place was the Gettysburg battlefield, four and a half months after the bloody and pivotal victory of the Union's Army of the Potomac over Gen. Robert E. Lee's Army of Northern Virginia. The event was the dedication of a cemetery for those who had died on those rolling fields. The wind was a two-hour speech by Edward Everett, a renowned orator and former senator from Massachusetts. And the fire was a dedication by President Abraham Lincoln that followed, a speech hardly more than two minutes in length. Like an ember left over from the conflagration of battle, it has warmed the nation's collective memory ever since.

Lincoln's Gettysburg Address represents perhaps the perfect combination of eloquence, elegance and economy in our history, shining rhetorical proof of the design axiom, "Less is more." Given the florid oratorical standards of the time, Lincoln's brevity could hardly have been expected. Yet a more reverberant effect cannot be imagined. Harry Rubenstein, chair of the division of politics and reform at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History (NMAH), sums up the occasion nicely: "Everybody says the same thing about the ceremony: Lincoln gave a great speech and Everett spoke for two hours."

A copy of that speech, in Lincoln's handwriting—the version generally regarded as the definitive text—is now on loan from the White House, displayed in the new Albert H. Small Documents Gallery at the reopened NMAH. It will be on view through January 4.

American schoolchildren have learned its cadences by heart for decades; many of us, young and nervous, recited it at patriotic ceremonies as our parents, proud and nervous, looked on. But the venerated address was not universally admired at the time. Eyewitnesses reported that there was silence when Lincoln finished, followed by sparse applause, once described by the late historian Shelby Foote as "barely polite."

It's possible that so soon after it began, hardly anyone realized that the speech had ended. Nor was the elegiac tone so appropriate to the occasion calculated to elicit the applause lines that presidential speechwriters seek today. It may seem surprising, too, that Everett, not the president, was the main speaker of the day. According to Rubenstein, the orator's top billing "made sense at the time. You're not going to ask a president in the middle of a major war to take the time to write a big speech."

The Chicago Times , no friend of Lincoln's, described the address as "silly, flat and dishwatery utterances," while the New York Times , strongly Republican at the time, praised it. The president himself is said to have harbored doubts about the speech. Everett was gracious. "I should be glad, if I could flatter myself that I came as near to the central idea of the occasion, in two hours, as you did in two minutes," he wrote to Lincoln the day after the ceremony. Rubenstein says it's possible that Everett was merely being polite, "but there's no way to know."

Lincoln later sent his fellow speaker a copy of the speech when Everett was assembling a book listing events at the battlefield dedication, to be sold for the benefit of wounded Union soldiers. The president wrote out by hand five copies of the address, two before the ceremony—historians aren't sure which of these is the copy from which Lincoln read at Gettysburg—and three afterward.

Lincoln's last handwritten copy, the only one signed by the president, was penned in March 1864, to be reproduced for a publication entitled Autograph Leaves of Our Country's Authors , which was also intended to raise money for the Union cause. One of the book's publishers, Alexander Bliss, kept the original document; it's the one now on display at the NMAH.

This copy remained in the hands of the Bliss family until Oscar Cintas, Cuba's ambassador to the United States in the 1930s, bought it at auction in 1949 for $54,000 (roughly the cost of a substantial New York suburban house at the time). Cintas, who died in 1957, had willed the copy to the United States. It is usually displayed in the Lincoln bedroom of the White House. The brief dedication made at Gettysburg, says Rubenstein, endures as nothing less than "a remarkable piece of literature."

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions .

Around the Mall: Old Documentary on Western Tribes Restored

Seattle-based photographer Edward Curtis had a singular passion. Beginning in the 1890s, he set out to document what he and most of his contemporaries believed was a "vanishing race"—that of the American Indian.

For 30 years, Curtis traveled across North America taking thousands of pictures of native people, often staging them in "primitive" situations. "There were many groups of what were considered exotic people living in North America, and he wanted to romantically and artistically render them as they existed in a traditional past," says Joanna Cohan Scherer, an anthropologist at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History and author of a new book of Curtis photographs. "Without question he is the most famous photographer of Native Americans from this period."

To raise money for his project, Curtis turned to Hollywood—sort of. In 1913, he traveled to the west coast of Canada to make a movie. Using members of Vancouver Island's Kwakwaka'wakw tribe (also known as the Kwakiutl) as actors and extras, Curtis documented local traditions and dances. "Pictures should be made to illustrate the period before the white man came," he wrote in 1912 to Charles Doolittle Walcott, Secretary of the Smithsonian, one of the project's sponsors. On the set, he paid Kwakwaka'wakw craftsmen to build traditional masks and costumes and even had the actors—most of whom had cut their hair European-style—wear long wigs. The film, titled In the Land of the Head Hunters , debuted in New York and Seattle in 1914 to critical success. But it was a box office failure. Audiences expected tepees and horses—not the elaborate, stylized dances and complex ceremonial masks of the Kwakwaka'wakw. "Because they weren't stereotypical Indians, people didn't know what to think of it," says Aaron Glass, an anthropologist at the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.

Recently, Glass and collaborator Brad Evans, an English professor at Rutgers University, set out to resurrect Curtis' film. A damaged partial print surfaced in the 1970s, but it was missing key scenes. In a half-dozen archives from Los Angeles to Indiana, the pair found film reels not seen since 1915 and discovered the film's original orchestral score (filed incorrectly in a drawer at the Getty Research Institute in Los Angeles). Last month, the restored film was screened at Washington, D.C.'s National Gallery of Art. An orchestra of Native American musicians, co-sponsored by the National Museum of the American Indian, performed the original score.

The culture that Curtis had thought was about to disappear still thrives, preserved by the descendants of people who acted in his film almost a century ago. Many of the ceremonies that Curtis used for dramatic effect—including bits of the symbolic and highly sensationalized "Cannibal Dance" —are still performed today. Curtis' film played a vital role in that preservation. Kwakwaka'wakw cultural groups had used fragments of the movie as a sort of visual primer on how their great-great-grandparents did everything from dancing to paddling huge war canoes. "We have a group of dance performers who are all related to the original cast in one way or another," says Andrea Sanborn, director of the tribe's U'mista Cultural Centre in Alert Bay, British Columbia. "The culture is very much alive, and getting stronger."

Post a Comment