Feeling Blue: Expressionist Art on Display in Munich

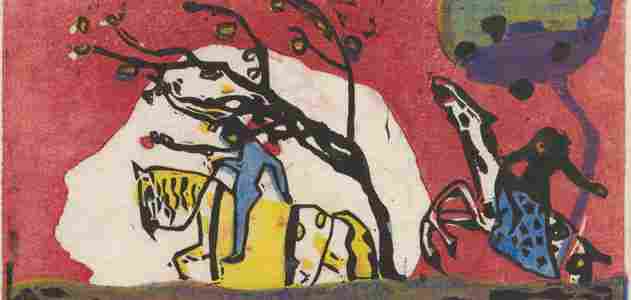

If you spot a blue horse on your next trip to Munich, chances are that you've either been enjoying too much of the local brew, or you're admiring the art at the Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus (State Gallery in the Lenbach House).

The Lenbachhaus, a small museum located northwest of the city center, pays homage to the Blaue Reiter (Blue Rider) group, a loose association of kindred spirits founded in 1911 by Wassily Kandinsky, Franz Marc and other artists. Though the group's collective work was cut short by the First World War, its ideas marked a major turning point in art history – the birth of Abstract Expressionism.

"Men are blinded. A black hand covers their eyes," Kandinsky wrote in an essay for the 1912 "Blaue Reiter Almanac," an unusual catalogue that combined a wide mix of art forms from many times and cultures.

The Blue Rider artists broke with tradition by rejecting objective ideas of what made art "good." What really mattered, they argued, was what each work of art expressed about its creator's inner state. Expression could take any form – a blaze of brushstrokes; a sprinkle of musical notes; a carved totem or a child's sketch – and the group's exhibitions and almanac showcased the gamut.

"We should never make a god out of form...it is not form (matter) that is generally most important, but content (spirit)," Kandinsky declared in the Almanac. "We should strive not for restriction but for liberation…only on a spot that has become free can something grow."

The Russian-born Kandinsky moved to Munich to study art when he was 30 years old, in 1896. It was a time when many new ideas – such as Jugendstil, a decorative style inspired by the arts and crafts movement -- were sprouting up amid the city's generally staid art scene, but Kandinsky didn't find his niche in any of them. In 1909, he joined a new group called the "New Artists' Association of Munich" where he met the German painter Franz Marc, who shared his view of art as a medium for personal and spiritual expression.

By 1911, Marc and Kandinsky were collaborating to publish an almanac that would be a kind of manifesto for expressionist artists. The name "Blue Rider" sounds a bit mysterious, but it was simply a title they came up with while chatting over coffee one day, according to Kandinsky.

"We both loved blue, Marc liked horses and I riders. So the name came by itself," he explained years later.

The first Blue Rider exhibition was thrown together hastily in December 1911, after the New Artists' Association rejected one of Kandinsky's paintings for its winter exhibition. Kandinsky and Marc, joined by the painter Gabriele Münter (Kandinsky's mistress of the past decade), left the group in protest and put together their own show -- literally right next to the NAA exhibition, since the gallery owner was a friend of theirs – which also included works by Robert Delaunay, Henri Rousseau, August Macke, and the composer Arnold Schoenberg.

Their eclectic exhibition was not well reviewed in the press, but that didn't stop the artists from organizing a second exhibition and publishing the Almanac the following year.

Kandinsky delivered a stinging rebuke to the critics in his essay about form: "The ideal art critic… would need the soul of a poet… In reality, critics are very often unsuccessful artists, who are frustrated by the lack of creative ability of their own, and therefore feel called upon to guide the creative ability of others."

The Almanac proved more popular than the publisher had expected, and a second edition was published in 1914. But although Marc and Kandinsky corresponded frequently about publishing a second volume, it never happened.

World War I broke out in 1914, forcing Kandinsky back to Moscow, where he stayed for the next eight years. Marc joined the German army, and died on a French battlefield in 1916, at age 36. Another Blue Rider painter, August Macke, was also killed in the war.

Kandinsky's career continued to evolve and flourish until the Second World War. He died in France at age 78, by then considered one of the founding fathers of abstract painting.

In 1957, Gabriele Münter celebrated her 80th birthday by donating her large collection of Blue Rider works to the Lenbachhaus. Today, visitors to the museum can contemplate Kandinsky's paintings inspired by folk art, Marc's mystical scenes of forest animals bathed in beams of color, and many works by other Blue Rider artists including Münter, Macke, Paul Klee, Marianne von Werefkin and Alexey von Jawlensky.

And yes, you'll even see some blue horses and riders.

NOTE: The Lenbachhaus is scheduled to close for major renovations in the spring of 2009, but for the next few months, it will be an even richer treasure trove than usual for Kandinsky fans with two special exhibitions. All of the artist's prints and graphic art – some 230 pieces – are on display at the Lenbachhaus through late February. And across the street, its sister gallery the Kunstbau is hosting a new Kandinsky retrospective in collaboration with New York's Guggenheim Museum and Paris's Centre Georges Pompidou. The exhibition will travel to Paris in April, and then on to New York in September 2009.

The Life and Times of a Maine Island

An island is a special place, often invested by both its residents and outside observers with an identity, a life and a personality. People talk and whisper, defend and attack, brag and condemn an island as if the landmass were a friend, family member or nemesis.

I don't know why islands inspire such personification or generate such strong opinions. Some people, including friends and relatives of mine, have stepped off the shores of Long Island and never again returned. Others leave for several years before coming back. And still others leave, but no matter how young they were when they sailed, they still consider it "down home."

For me, even more than an island or a hometown, Long Island is a family and a heritage. I was born an eighth-generation islander. I am unapologetically proud to say my family built the island community and has helped sustain it for going on 200 years.

The family flourished and failed and feuded on the shores of Long Island. They were keen business operators, tireless workers, layabouts, bandits, alcoholics, church workers, community leaders, detached, mean, congenial and fun-loving along the banks of a harbor that bears the family name and on hillsides that contain the bodies of their forebears.

It is a heritage that to people from other states sometimes inspires a certain amount of intrigue, bewilderment and snobbery. The myths, both positive and negative, about islands—and Maine itself, for that matter—are legion. Residents of both are alternately portrayed as crusty fisherman, sturdy woodsmen, wizened sages or drunken, backward hicks.

Certainly, some spiritual justification exists for all this. An island does seem to possess, and can potentially lose, a unique life force. Some 300 year-round Maine island communities, although many consisted of no more than a few families, have died over the past century or so. Yet, more than 250 years after it first appeared on nautical charts and nearly two centuries after settlers built the first log cabins, Long Island survives. Out "amid the ocean's roar," as one writer put it, Long Island is one of only 15 Maine islands that still support a year-round community. And it is one of the smallest and most remote.

The island itself lies in Blue Hill Bay roughly eight miles southwest of Mount Desert Island, but a world away from the tourist-driven economy of Bar Harbor and the posh estates of Northeast Harbor and Seal Harbor.

The working-class village surrounding Bass Harbor is the closest mainland port and the one most frequently used by Long Islanders. On the run from Bass Harbor to Long Island, three main islands are clustered in the first four miles: Great Gott Island, Placentia Island and Black Island. All three once supported year-round communities, but now Great Gott has summer residents only, Black has one house and Placentia is abandoned.

Because of its spot along the outermost line of Maine islands, Long Island was usually called Outer Long Island and sometimes Lunt's Long Island in the 1800s to distinguish it from a similarly named island closer to Blue Hill. Starting in the 1890s, the village on the island became known as Frenchboro, named after a Tremont lawyer who helped establish the island's first post office.

The community of about 70 year-round residents sits on or near the sloping banks of Lunt Harbor, a long horseshoe-shaped inlet that provides protection from all weather but a northeast wind. The sheltered and accessible harbor is one reason why Long Island has survived while other island communities have died.

Lunt Harbor opens toward Mount Desert Island with the Mount Desert hills looming ghostlike on the horizon. On summer nights, you can sit on a wharf and watch headlights from cars full of tourists as they climb to the peak of Cadillac Mountain, high above Acadia National Park.

The banks make sharply away from Lunt Harbor, providing a perch for mostly modest homes to sit in quiet observance of the daily goings and comings.

The island has just over one mile of paved road that starts at the ferry pier and runs around the cove to Lunt & Lunt Lobster Co., the island's only full-time business. Along the way, the road passes the Frenchboro Post Office, the Frenchboro Historical Society, Becky's Boutique, the Long Island Congregational Church and the Frenchboro Elementary School. The church and school were built in 1890 and 1907 respectively. There is no general store.

Leaving the harbor, paths and dirt roads wind through sometimes-pristine spruce forests, past bogs, lichen-covered ledges and small mossy patches where evergreen branches have given way to occasional glimpses of sunlight. There is little warning before these paths empty onto the island's granite shores, and suddenly the confining, sometimes claustrophobic woods give way to the mighty Atlantic.

The main trails are actually old logging roads. These dirt roads run to Eastern Beach, the Beaver Pond, Southern Cove and partway to Richs Head, the island's most distinguishing geographic feature and its easternmost point. The roundish Head, connected to the main island by a narrow neck of rocks, is exposed to the open sea.

Settled by William Rich and his family in the 1820s, Richs Head hosted the island's only other village for almost 80 years. It was abandoned by the turn of the century. Only the slight depressions of hand-dug cellars near former farmland suggest that three generations of pioneers lived, worked and raised families there.

I find it strangely sad to read about the historic deaths of the once common island communities, killed by progress and a changing way of life, during the 19th and early 20th century. Many have vanished without a trace. Some days, as I stand in my father's lobster boat and sail past the now deserted Placentia and Black Islands and even the summer colony of Great Gott Island in Blue Hill Bay, I am enveloped by a sense of melancholy.

On Black, I envision the railways that once carried granite from quarries to waiting vessels. I imagine old man Benjamin Dawes, an island pioneer in the early 1800s, ambling across the shore to his fishing boat. Or my great great great grandmother, Lydia Dawes, building castles as a child on the sandy beach along Black Island pool. Knowing a community once existed makes the island seem even older and more lifeless—like the once-bustling house on the corner that stands silent and empty, save for drawn curtains and dusty dishes stacked in cobwebbed cupboards. You just know that life will never return.

I no longer live in Frenchboro; college, work and life have carried me across New England and New York to explore other places for awhile. This exploration has been fun and enlightening and no doubt provided some clarity to island life, something to which I someday will return. Still, for nearly 23 years Long Island fit me like a second skin. I knew its landscape by touch, smell and intuition. From the well-trodden woods behind my house to the deer paths that wound through huckleberry bushes to the Salt Ponds to the tumbled beach rocks of Big Beach, I knew the land. I knew the smell of moss, the hidden brooks, the cracked ledges, the shoreline and the unique trees. I was baptized in the harborside church, educated in the one-room school, consumed by daydreams on Lookout Point and engaged on the sloping granite of Gooseberry Point.

For two months in July and August, Lunt Harbor is filled with yachts, their passengers taking advantage of the relatively easy and scenic walking trails. Or they might just sit and soak in the nighttime quiet broken only by the lapping of water against hull or the occasional clanging of Harbor Island bell.

On such crisp island evenings, which require sweatshirts even in August, you can look up into the clear night sky, and see more stars than you ever knew existed. In fact, they seem so numerous and hang so close it seems you can almost reach out and touch Heaven itself.

This is an adaptation from chapter one, "Long Island Maine," of the book, Hauling by Hand: The Life and Times of a Maine Island by Dean Lawrence Lunt (paperback), Islandport Press, 2007.

What’s Up From the Smithsonian

Close to the Heart Photographic jewelry, including pocket watches adorned with babies' photos and brooches bearing lovers' likenesses, was all the rage in the mid-1800s. See these keepsakes at the National Portrait Gallery, October 24.

Colorful Statement Fritz Scholder's paintings examine his mixed Indian heritage. His works, on view for the first time since his death in 2005, are at the National Museum of the American Indian's D.C. and New York City locations, November 1.

Sinful Dealings Set in Jerusalem's back alleys and millionaire mansions, Nina Burleigh's Unholy Business , from Smithsonian Books, relates the intriguing story of the Holy Land's most infamous relic, the James Ossuary, as it goes from acclaimed biblical artifact to disgraced modern forgery.

Garden View Until now, only maharajahs had seen the garden paintings that festooned the Indian royal palaces at Jodhpur. Starting October 11, the Sackler Gallery showcases 61 of them.

Vision and Verse Elihu Vedder illustrated his 1884 translation of The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam with graceful drawings, now on display in a traveling exhibit beginning November 14 at the Phoenix Art Museum.

Post a Comment