Ivory Merchant

Among the more than 3,000 songs that Irving Berlin wrote was a tune called "I Love a Piano." A lyric from it goes:

"I know a fine way to treat a Steinway I love to run my fingers o'er the keys, the ivories..."

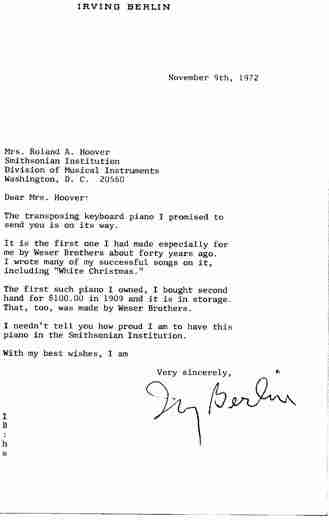

Of course Berlin (1888-1989), who was born 120 years ago this month, had lots of reasons to love a piano: during a long and glittering career, he created such enduring classics as "Alexander's Ragtime Band," "White Christmas," "God Bless America," "Easter Parade" and "Puttin' on the Ritz." A self-taught pianist, he may have tickled the ivories, but he played mostly on the ebonies. And the pianos he used for composing weren't Steinways but specialized transposing pianos. A lever moved the keyboard, causing an inner mechanism to alter notes as they were played into any key he wanted. In 1972, Berlin donated one of these curious devices, built in 1940, to the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History (NMAH).

Dwight Blocker Bowers, an NMAH curator and a musician himself, has played a few tunes on Berlin's piano. "The period around the turn of the century was an age of musical machines and the transposing piano was one of them," he says. "Berlin had a few of these pianos. He called them his ‘Buicks,' and when I worked the mechanism to move the keyboard, it played like an old stick-shift car drives."

Berlin's reliance on the black keys meant he was able to play only in the key of F sharp. It turned out to be a liability. "It's very difficult to play in F sharp," according to pianist-vocalist Michael Feinstein, a preeminent interpreter of America's 20th-century songwriters. "It is a key that is technically limiting."

Berlin's life story—Dickens by way of Danielle Steel—clearly demonstrates, however, that the composer had a gift for overcoming limitations. Born Israel Beilin in Russia, he immigrated to New York City with his family five years later; his father, employed as a cantor in synagogues, died in 1901. As soon as the boy was old enough, he began selling newspapers and busking on the streets of the Lower East Side. As a teenager working as a singing waiter at Pelham's Café in Chinatown, he was asked to write lyrics for a song to compete with other musical restaurants. The result was "Marie From Sunny Italy," and when it was published, it earned the kid 37 cents and a new name: I. Berlin, the result of a misspelling.

Having watched the café's pianist compose "Marie," Berlin promptly sat down and taught himself to play, on the black keys. "It's peculiar," says Feinstein. "Most people would probably start playing in C, on the white keys. It probably wasn't a choice; he started hitting the black keys, and that's where he stayed." Feinstein adds: "What's remarkable about Berlin is his evolution. Listening to ‘Marie From Sunny Italy,' you wouldn't think that there's a musical future there."

Berlin wrote both the music (in F sharp, naturally) and lyrics for the first of his huge hits, "Alexander's Ragtime Band," in 1911. But F sharp was not the key that sheet music publishers wanted—hence the need for a piano that would produce his popular tunes in popular keys.

Berlin's stick-shift Buicks were the medium but not the message. "I don't think [the transposing piano] affected the music itself," says Bowers. "It just let him translate what he was hearing in his head." And what Berlin heard in his head, millions have been hearing in their hearts for nearly 100 years. Once asked about Berlin's place in American music, composer Jerome Kern responded: "Irving Berlin has no place in American music—he is ‘American music.'"

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions .

Model Arrangement

Writers as diverse as Norman Mailer and Gloria Steinem have waxed lyrical about Marilyn Monroe's enduring appeal, but they have rarely doted on her movie performances. Instead, they consider her image in photographs: the playful, precociously sexual Norma Jeane, so carefully cloaking her harrowing childhood; the iconic platinum-blonde glamour girl who wanted only to marry a millionaire; the dreamy and heartbreakingly worldly woman of the fabled "Last Sitting," photographed six weeks before she died. One could say that her greatest role was a nonspeaking one: Marilyn, the Portrait.

"She could, arguably, be the most photographed person of the 20th century," says producer and director Gail Levin, whose PBS "American Masters" documentary, "Marilyn Monroe: Still Life," aired in 2006, the year its subject would have turned 80. In justifying how Monroe could qualify as an "American Master"—she was technically not the artist, but rather the artist's muse or model—Levin told an interviewer, "Not only did she master her own image, create it and ultimately control it, she was the subject of many of the great masters of photography of the 20th century." One of these was fashion photographer and portraitist Milton Greene (1922-1985), whose photos reveal a little-recognized turning point: the moment at which Monroe began to take control of both her image and her life.

Ironically, Greene's photographs—such as the winsome shot from his 1954 "Ballerina" series shown here—have been at the heart of a legal struggle over who owns the rights to images of celebrities. Is it the photographer who obtained a model release, made the photos and holds the copyright for them? Or is it the subject or his or her heirs? In Monroe's case, the company Marilyn Monroe LLC—controlled by Anna Strasberg, widow of acting coach Lee Strasberg, to whom Monroe left her estate—asserted a "right of publicity" to her image but lost in California and New York courts. The stakes were not trifling: Monroe has made Forbeom's list of "Top-Earning Dead Celebrities" every year since it was inaugurated, in 2001. She was ninth last year, with earnings of $7 million.

When Monroe laid claim to her image for the first time, in the 1950s, Greene was her co-conspirator. They met on a shoot for Look magazine in 1953 and "became instant friends," says Greene's son Joshua; soon they hatched a plot to free Monroe from her restrictive contract at 20th Century Fox, and she left Hollywood, moving in with the Greene family in Connecticut for a time. In this haven, Joshua Greene says, Monroe and his father formed their own company, Marilyn Monroe Productions, which in 1956 co-produced with Fox (under a new contract that gave her more control over her career) Bus Stop , the first film to showcase her dramatic capabilities.

Meanwhile, Greene was photographing Monroe—in Connecticut, New York and Los Angeles—in ways she had not been photographed before. They raided studio costume departments for whimsical outfits; they grew playful with settings and moods. "Everything leading up to 1953 was either on-set photography or glamour shots," says Joshua Greene. "My father was determined to break that mold and capture the real person, the soul, the emotion. He wanted to show the range of her capabilities as an actress."

A radiant, natural, wistful Monroe emerged from these improvised sessions. In the "Ballerina" series, for instance, her tulle dress was too small to fasten so she clutched it in a gesture of instinctive diffidence, evoking both the demure child and the voluptuous siren. In addition to other studio sessions, Greene took a multitude of candids—at cocktail parties, in front of the Greene Christmas tree and, eventually, at Monroe's private wedding to Arthur Miller in 1956.

Monroe reportedly once described Greene as unique in her life: a male friend and protector who treated her with respect. The pictures reflect that relationship, says Carol Squiers, a curator at the International Center of Photography in New York City. "Marilyn never had a father, and she shuttled between foster families," Squiers says. "Milton incorporated her into his family. He provided a kind of sanctuary that was both professional and personal. She trusted him and relaxed with him, so there's not that sex-goddess tension you see in most Marilyn pictures."

By 1957, however, their relationship was all but over—Joshua Greene says his father and Miller differed over the direction of Monroe's career (though she also accused Greene of having mismanaged their company). One oft-repeated story from the fraught set of The Misfits (1961), her last completed film, has her shrieking at Miller in the last throes of their marriage: "You took away the only friend I ever had! You took away Milton Greene."

The photographer and his muse spoke to each other only one more time, on the phone a month before Monroe died, at age 36 on August 5, 1962. "They were both happy to renew the friendship," Joshua Greene says. They planned to meet when Greene returned from shooting the Paris fashion shows that fall. But by then she was gone.

Michelle Stacey , an editor-at-large for Cosmopolitan , is the author of The Fasting Girl: A True Victorian Medical Mystery .

David Roberts on “The Brink of War”

David Roberts received his Ph.D. from the University of Denver and taught for nine years at Hampshire College before embarking on a career as a freelance writer that has spanned almost thirty years. During that time, he has produced several books on Native Americans and the American West, including Devil's Gate: Brigham Young and the Great Mormon Handcart Tragedy , due out this September.

What drew you to this story? Could you describe its genesis? I was doing research on the Mormon handcart tragedy when I came across information about Brigham Young sending out missions to the Indians in 1855. The great question is: "What were these missions about?" Were they, as alarmists claimed at the time, about actually trying to recruit Indians as allies to fight the government?

The United States came within a whisker of invading Utah in 1858 and starting a civil war three years before the Civil War. Because the conflict ended up fizzling out, it's not the most dramatic story about the West. It comes across as a huge anticlimax, but it was a beneficent one, because it would not have been pretty if we had tried to wipe out Utah. All these amazing events that happened in the 1850s in Utah really intrigued me and I think most readers will be greatly surprised to learn about them.

What was your favorite moment during reporting? I started out my research by flying to Las Vegas. There is a partially reconstructed fort in downtown Las Vegas, which nobody ever visits, but which recreates the original mission. In fact nobody realizes that Mormons were the first Americans to settle Las Vegas.

Trying to see the landscape from the point of view of these very scared missionaries, I retraced by auto the routes they had followed in 1855. If you drive into Moab from the north you just cruise in on a highway. Right at Arches National Park, the highway blasts through what was once a cliff and you don't even notice it. The Elk Mountain missionaries there had to actually take their wagons apart and lower them down this cliff. I stood in the parking lot at Arches and studied the cliff and tried to imagine these guys. They could see the Colorado River in the distance and knew it was the place where they wanted to build, and they're taking their wagons apart and lowering them and putting them back together. That kind of on-the-ground retracing and re-imagining was really fun.

Post a Comment