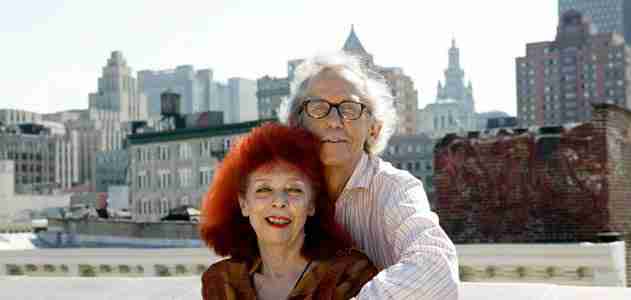

Q and A: Christo and Jeanne-Claude

In 1976, installation artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude built Running Fence , a 24.5-mile fabric divide that sliced through Northern California's Sonoma and Marin counties. They spoke with Anika Gupta about a forthcoming Smithsonian exhibit on the project.

Why did you choose Northern California as the site for Running Fence ? Christo: The moisture [in Marin County] creates this lovely light and beautiful fog. In the morning, the mist rolls forward from the ocean and the fence becomes invisible, part of the mist. Then the mist rolls back. So throughout the day the fence is constantly appearing and disappearing.

Running Fence stretched across private land, most of which belonged to 59 ranchers. How did you get them to agree to let you use their land? Jeanne-Claude: I was standing in this one kitchen and the rancher kept saying to me, "The fence has no purpose." So I told him, "A work of art needs no purpose, it is beautiful." But he was not totally convinced. Then, as he led me to the door, I saw these little green leaves by his front stoop. "What did you plant here, lettuce or radishes?" I asked. "Those are flowers," he explained. "But you cannot eat flowers!" I responded. And he said, "Honey, I got the message."

What was your reaction when the Smithsonian American Art Museum purchased the Running Fence documentary and related photos and drawings? Christo: We were very excited, of course. We were eager that the project stay in the United States, and that it remain a complete story.

You later encountered very vocal opposition to the project. Why? Jeanne-Claude: The opposition said that the things we did were not art. Someone even claimed that we were Soviet spies building a marker for missiles. We later realized the local artists saw us as an invasion of their turf, which is quite a human response.

Running Fence is not the first of your projects to be featured in a documentation exhibition. How did the possibility of an exhibition change your artistic process? Christo: At the beginning of the project, we kept 60 of the early sketches for the exhibition. We also kept a scale model [68 feet long]. At one point, we promised the ranchers that they could keep all the fence materials after "Running Fence" was done. But we kept one of the poles and one of the fabric panels ourselves for the exhibition.

When you called your project Running Fence , were you thinking of the role that fences play in the West? Christo: No. At first we were going to call the project the Divide, after the Continental Divide, because that is what inspired us to build it. We were up in the Rocky Mountains and we saw the sunrise over the Continental Divide. But then we thought, Divide is too unfriendly a word. We wanted to link the suburban, urban and highway cultures in California together rather than separate them. Also, that name was vague. We prefer very descriptive titles. So then we chose "Running Fence."

Jeanne-Claude: We do not think of it as a fence. It does not have a beginning and an end. It has two extremities, like a person.

Stardust Memories

Space enthusiasts can now get an up-close look at the latest extraterrestrial explorer. In 2006, NASA's Stardust capsule returned from a seven-year, three-billion-mile trip to collect dust from comet Wild 2—the first mission to bring home a piece of the solar system from someplace other than the moon. Measuring just 32 inches in diameter—not much bigger than a standard car tire— Stardust was fitted with a special arm topped with squishy gel patches to collect comet particles without damaging them. "Like bugs on a windshield, except the [bugs] didn't get crushed," is how Air and Space Museum senior curator Roger Launius described the delicate collection process. NASA scientists will sift the comet dust for clues about the elemental makeup of the outer solar system. The stellar dust might even reveal how the composition of stars has changed over time, leading to insights into the origin of the universe. The capsule went on permanent display at the museum's "Milestones of Flight" exhibit on September 24.

Roy Lichtenstein: Making History

The pop artist Roy Lichtenstein created the 31-foot-tall aluminum sculpture Modern Head in 1989. Its owner, the James Goodman Gallery in New York, lent it to New York City's Battery Park in January of 1996. On September 11, 2001, the Head sustained no serious damage, although it was just one block from the World Trade Center. Federal agents sifting through the ruins left messages for each other taped to the Head 's base. After 9/11, the sculpture moved to the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Coral Gables, Florida, where Samuel Rose, a commissioner for the Smithsonian American Art Museum (SAAM), encountered it. He arranged for the six-and-a-half-ton piece to be installed at SAAM's southwest corner, near the F Street entrance, where it will greet visitors for the next six months. "Our interest is in the Head as art," said SAAM curator George Gurney. "But its connection to September 11 does make it unique in our collection."

Post a Comment