Botticelli Comes Ashore

"How much do you want a Botticelli?" The question was sent to Isabella Stewart Gardner in Boston in a letter posted by Bernard Berenson on August 1, 1894, from London. Berenson, thirty-one, had, with the publication of the groundbreaking Venetian Painters of the Renaissance , recently established himself as an expert on Italian art. Four months before, he had sent Gardner a copy of his book, and earlier that summer, when she was in Paris, he urged her not to miss an exhibition of English pictures.

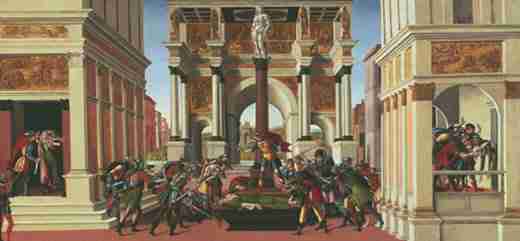

Soon after, Isabella Gardner asked Berenson his opinion of several Italian Old Master pictures proposed to her by dealers in France. Berenson replied that the paintings were not what these dealers claimed and offered her the Botticelli instead. "Lord Ashburnham has a great one—one of the greatest: a Death of Lucretia ," he wrote. But, he "is not keen about selling it." Yet, Berenson thought that "a handsome offer would not insult him."

Berenson also named a price: "about £3,000," or some $15,000. He added, "If you cared about it, I could, I dare say, help you in getting the best terms."

Isabella Stewart Gardner had made her first major purchase of an Old Master painting two years before, on December 5, 1892, at the Paris auction of the collection of the late Théophile Thoré. The day before the sale, an artist friend had accompanied her to peruse Thoré's art, and there she saw the three Vermeers that were to be auctioned. To bid for her, Gardner hired Fernand Robert, a Paris antiques dealer. At the time, auctions generally operated as a wholesale market, where dealers acquired stock. If they knew that a collector wanted a particular work of art in a sale, they would try to buy it in hopes of selling it to the collector immediately afterward.

The first Vermeer in the Thoré auction, A Young Woman Standing at a Virginal , went to a Paris dealer, Stephen Bourgeois, for 29,000 francs. Bidding for the second, The Concert , again climbed to 29,000 francs, and Fernand Robert won the picture.

"Mrs. G. bought the van der Meer picture for fr. 29, 000," John Lowell "Jack" Gardner, Isabella's husband, noted matter-of-factly in his diary.

No doubt The Concert struck Isabella Gardner because of its understated, well-plotted beauty. The small picture was a Dutch interior where two young women, one in a glimmering white skirt seated at a harpsichord, and a young man in a brown jacket with a lute, are performing a piece of music on the far side of a room, across a floor patterned with black- and- white squares. On the wall behind them hang two large Dutch Old Masters in black frames. In the complex interlocking of colors and shapes made from the musicians, the instruments, the fabrics, the paintings, and the furniture, some in shadow and others in light, Vermeer captured the fleeting enchantment of the music, translating the elusive spell of one art form into another. Gardner's new acquisition was the first Vermeer to reach Boston and the second in the United States. With a commission, the canvas cost Gardner 31,175 francs, or just over $6,000. Although Henry Marquand had paid only $800 for his Vermeer five years before, Gardner's purchase soon looked like a bargain.

In August a friend reported that a Dutch art expert "says your concert is now worth easily between 150 and 200 thousand [francs]!" Indeed, soon after, Stephen Bourgeois turned around and sold his Young Woman Standing at a Virginal to the National Gallery in London for 50,000 francs, or $10,000. Prices of Old Master pictures were rising.

Still, in the mid-1890s, the number of Americans buying Old Masters remained small. Gardner's purchase at a Paris auction showed her independence of mind and her ambitions as a collector—and that she had her ear to the ground among progressive artists in London and Paris. In proposing the rare Botticelli to Gardner, Berenson knew well she was likely to leap at the chance to acquire it. She had definite, individual taste, with particular likes and dislikes. She had spent several summers in Venice and was drawn to the art of the Italian Renaissance. Rembrandt was the favorite artist of America's tycoons, but not hers. "You know, or rather, you don't know, that I adore Giotto," she wrote Berenson in 1900, "and really don't adore Rembrandt. I only like him." He shared her pioneering taste for Italian art and sympathized: "I am not anxious to have you own braces of Rembrandts, like any vulgar millionaire," he wrote. A devout Anglican, Gardner had no problem with religious imagery. The same summer she won the Vermeer, she had also purchased a Spanish Madonna and a Florentine Virgin and Child . Soon she spelled out her wish to buy Italian pictures, claiming that a Filippino Lippi and a Tintoretto (along with "a Velasquez [ sic ] very good") were her "foremost desire always." She added: "Only very good need apply!" Unlike Marquand, Gardner was buying for herself, her own plea sure, and her Beacon Hill house, where she hung both new and old paintings and propped the extras on chairs. Like Marquand and even more emphatically than him, she insisted upon masterpieces.

When Berenson proposed the Botticelli, Isabella Stewart Gardner was fifty- six, slim, and elegant. She directed her life with a theatrical sense of style. She had pale skin, dark hair, an oval face with almond- shaped eyes, a long straight nose, and a full, awkward mouth, which, like her eyes, curved slightly down and suggested the seriousness that, for all her flamboyance, was at the core of her personality. She had a long neck and an erect carriage. She wore well-cut clothes (many designed by Charles Worth and imported from Paris), which spoke to her love of textiles but also to her creativity and skill in shaping her own image. In a black- and white photograph, she stares out with a mix of wisdom and innocence, her willowy figure clad in a fitted dress of dark watered satin with a high collar, long sleeves, and buttons running straight down its front. In summer, she wore large- brimmed hats festooned with veils that she tied down around her neck. Perhaps increasingly self- conscious about her face, she covered it as she aged. In her sixties, she would maintain her narrow form, holding her neck straight and her head high.

Energetic and self- possessed, Isabella Gardner was a New Yorker who cut her own path in Boston, breaking the establishment rules in dress, social practice, and collecting. Her marriage to Jack Gardner, a Boston Brahmin, brought her to the top of Boston's social hierarchy and gave her the freedom to shape her own role as a visible patron of advanced art. She is "the most dashing of fashion's local cynosures," as one critic put it, "who can order the whole symphony orchestra to her house for a private musicale."

Diva and muse, she gathered about her a circle of artists, writers, and musicians—young men whose careers she championed, who kept her up with their work and who were drawn to her larger- than- life persona. "She lives at a rate and intensity," Berenson wrote, "and with a reality that makes other lives seem pale, thin and shadowy." But after three de cades in Boston, Gardner still described herself as a "New York foreigner." Indeed, Boston society never embraced her, and she in turn exploited her outsider identity to fullest advantage. If Bostonians frowned on extravagance, she spent freely on clothes, jewelry ($83,000 on a necklace and a ruby ring), and concerts. By traveling frequently in Europe and making a habit of summers in Venice, she joined a circle of influential American expatriates, including not only John Singer Sargent but also James McNeill Whistler and Henry James, who in various ways encouraged her collecting.

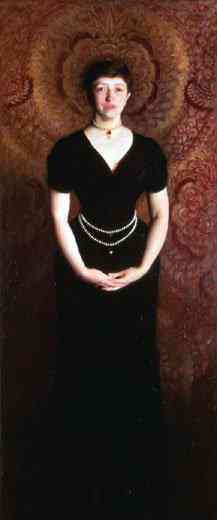

In 1886, Henry James had taken Isabella Gardner to Sargent's London studio specifically to see the notorious portrait Madame X . Far from frightened off, Gardner commissioned Sargent to paint her own portrait, which he began immediately after he finished painting Elizabeth Marquand. Where he had portrayed the wife of the Metropolitan Museum's president conventionally and naturalistically, as an American aristocrat smiling and seated in a chair, he turned Isabella Gardner into an icon, a symmetrical image set before a hanging of Venetian brocade with a radiating pattern of red, ochre, and gold, designed to convey her singularity as a devotee and patron of art. She stands, facing us straight on in a long black dress with a low neck and short sleeves, her shoulders drawn back and her hands clasped so her white arms form an oval. Henry James suggested the artifice of the Sargent portrait when he described it as a "Byzantine Madonna with a Halo." Sargent showed the portrait in his first American exhibition at the St. Botolph Club on Boston's Beacon Hill, entitling it "Woman, an Enigma." What shocked Boston were the ropes of pearls around Gardner's neck and waist, and the décolletage of the dress. In her slightly parted lips and her bold gaze, Sargent also suggested Gardner's engaged presence and quickness of mind. The artist painted the portrait six years before Gardner bought the Vermeer, but his tribute to her as a high priestess of art was one she embraced. Her appetite for art was not a pose but a passion; aestheticism became the guiding principal of her life. Given money, she acquired paintings, sculpture, antique furniture, and other decorative arts—casting herself by means of her collection as a Renaissance patron, and taking the domestic environment to which she as a woman was restricted and turning it ultimately into a public space designed to display art and express herself as a collector. "Mrs. Gardner's collecting seems to have been part of a strategy" the art historian Kathleen Weil-Garris Brandt has written, "that developed to win for herself as a woman, albeit a rich and powerful one in Victorian Boston, the freedoms, the self-definition, and—crucially—the social and intellectual respect which she believed her Renaissance woman models to have enjoyed."

Later, when Gardner built the museum where she also lived, she placed above the door a coat of arms, with a phoenix, and into the stone carved the words "C'est Mon Plaisir"—It Is My Pleasure. The phrase was not simply a declaration of ego ("the justification for her every action," as one biographer put it), but resonated with the aestheticism of the nineteenth century and summarized the creed that art above all involved sensuous plea sure and spiritual enlightenment.

In December 1894, four months after Berenson had written Isabella Gardner about Lord Ashburnham's Botticelli, they met in Paris and went to the Louvre together. The following day, she agreed to buy the painting from him for 3,000 pounds, or $15,000—more than twice what she had paid for the Vermeer. The Death of Lucretia was the first Botticelli to travel to America. The painting was richly colored—a scene with small figures set in an open square framed by monumental classical buildings. Lucretia is a young woman in a green dress prostrate on a tomb, a knife in her chest, surrounded by soldiers who have discovered her suicide. In addition to conveying the emotion of the charged encounter, Botticelli also conclusively demonstrates his abilities to create the illusion of space with linear perspective in the setting of the scene. Later, the art historian Laurence Kanter described it as "certainly one of the great masterpieces of Florentine painting from the last years of probably its greatest period, the golden age of the fifteenth century." With the Botticelli, Isabella Gardner took American collecting in a new direction, and her collaboration with Bernard Berenson began. She enlisted him as a scout for Old Masters and agreed to pay him a 5 percent commission on the price of each purchase. As dealers typically charged commissions of 10 percent when they acted as brokers, she thought she was getting Berenson's advice for a bargain. At least in the short run, she would be wrong.

Reprinted by arrangement with Viking, a member of Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from Old Masters, New World by Cynthia Saltzman

Copyright © Cynthia Saltzman, 2008

Brooklyn Museum of Art vs. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

From the exhibition Zen Mind/Zen Brush: Japanese Ink Paintings from the Gitter-Yelen Collection at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston

To get ready for the fall season, I found out what is coming down the pike at two museums that have been really great to visit in the past year or so. Let the slugfest begin.

Museum of Fine Arts, Boston has four shows headlining their fall roster. The first is an exhibition of Assyrian art traveling from the British Museum. Yes, a slow start, but they follow that up with a look at the career of celebrity photographer Yousuf Karsh, who shot everyone from Albert Einstein to Audrey Hepburn to the Kennedys. The third act is a small show of Japanese ink paintings, which looks a lot more interesting than it sounds. Rachel Whiteread runs the last leg of the race. The last show of the season is devoted to her most recent work, Place (Village), which is an installation of handmade dollhouses.

The Brooklyn Museum of Art starts with an exhibition of four short films from Jesper Just. Their second show pulls together 40 works from the museum’s growing contemporary collection, specifically pieces that were made after 2000 and resonate with the museum’s rich ethnic and artistic locale. After that, the last stop of an international tour of the work of Gilbert & George arrives. This could be the sleeper, as there are 80 or so stellar works in this retrospective. The final exhibition brings together feminist works that comment on the “house”—whether the historically male-dominated museum or the home as the principal domain of women.

Put side by side like this, I’m torn about which venue comes out on top. And choosing a winner before actually seeing any of the shows is probably foolhardily premature. But I'm ready and willing to take bets.

Flag-Waving Artists

Who knew head-in-the-clouds artists with strong patriotic sensibilities were out there? They are -- and they have been for some time. And I’m not just talking about Jasper John’s canvas homage to the red, white and blue.

Not quite a founding father, but a powdered wig type all the same, Charles Willson Peale blended soldiering and portraiture during the Revolutionary War. One of the Sons of Liberty, he not only fought in the war, he also documented many of its players, including Thomas Jefferson, Lewis & Clark, John Hancock and Alexander Hamilton. George Washington sat more than a half-dozen times for Peale, allowing the artist to create almost 60 portraits of the first president.

In World War II, the U.S. Army recruited artists and designers to fight the Nazis with smoke and mirrors. One of the young soldiers was the eventual abstract expressionist Ellsworth Kelly. During his tour, Kelly helped develop prototypes of fake tanks, jeeps and weaponry made out of rubber, burlap and wood. These were set up in strategic places to convince the Germans that the Allies had more soldiers on the ground than they really did.

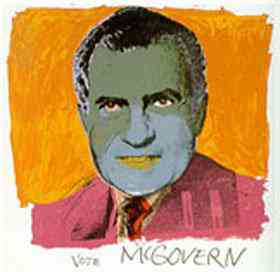

Andy Warhol practically stumped for the Democrats. He made a multi-colored print of Richard Nixon in 1972 with the caption “Vote McGovern" underneath the portrait. If only the print had been stamped on campaigning buttons and posters. Things might have turned out differently for George on Election Day. Nixon was certainly not looking like someone I’d let kiss a baby or shake my hand, not with that desiccated greenish-blue tint to his face. And the beady yellow eyes didn’t help matters. And most subliminal of all, the portrait was set against a background of the political hot-button color of pink (gasp!).

Post a Comment