Making History

Animals are usually the "guinea pigs" for human medicine, but a recent case at Smithsonian's National Zoo worked the other way around. After inventing a procedure that reverses vasectomies and performing it on about 13,000 patients, St. Louis-based urologist Sherman Silber successfully operated on a critically endangered species at the zoo. "Minnesota," a Przewalski's horse kept there since 2006, had been vasectomized to keep him from horsing around in the co-ed enclosure at his previous home. The species became extinct in their native Central Asian habitats about 40 years ago, and there are only 1,500 are alive today. When the zoo's Budhan Pukazhenthi, a reproductive specialist, realized that Minnesota's genes made him an ideal sire, he asked Silber to team up with the zoo's veterinary staff. "To maybe bring an extinct animal back from extinction was pretty thrilling," Silber says. Minnesota will be introduced to a mate this summer.

From Antony Gormley, Plinth Power

Artist Thomas Schuette's Fourth Plinth project "Model for Hotel 2007"

I’ve never seen any of the works in person while they were up, but I have a soft spot for the Fourth Plinth of Trafalgar Square all the way over in London. Some critics grouse that the works that adorn the column always fall short in someway, but it gets contemporary art out in public in a very well known venue, so quit the whining.

There have been several sculptures put up since it started in 1999. Mark Wallinger produced a life-size sculpture of a man that ended up looking miniscule in comparison to the height of the plinth. Rachel Whitehead made a cast of the plinth and inverted it on top of the column. Marc Quinn carved a marble bust of the torso of Alison Lapper, an artist born without arms who was pregnant at the time.

The latest evolution comes from Antony Gormley, and is set to take the stage in November. The artist will put a giant soapbox on top of the plinth and allow people to climb up (actually, they’ll get carried up by crane) and chat, rant or rave about whatever they like to the visitors of the square for one uninterrupted hour. The performers chosen must first apply online; so far I haven’t found where, but my hope is that the applications and the project itself will stream live so that those of us on the other side of the pond can finally get a front row viewing.

It’s in the Bag

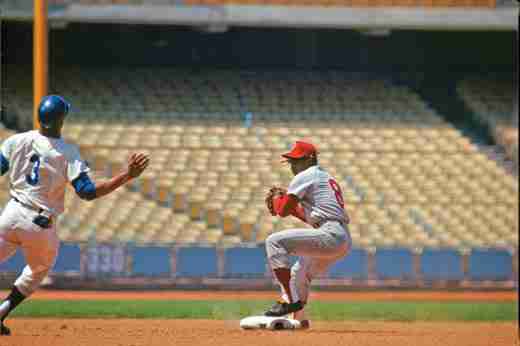

More than the home run, more than the strikeout, the double play distills the physicality of baseball. The instant the ball is hit, the fielders strive for timing and precision; the base runners strive for speed and disruption. When the lead runner launches himself cleats-first toward second base, it's like flashing a switchblade during a pas de deux.

Neil Leifer may appreciate the moment more keenly than even some of the countless major leaguers who have executed the double play over baseball generations. In 1965, Leifer figured out how to get a worm's-eye view of one. His ingenious methodology yielded just one image, but that was enough to capture what no photographer had captured before.

Leifer is both an artist and a techie, with an eye for iconic moments and a head for inventing ways to capture them. When the Houston Astros started playing in a domed stadium in 1965, he was quick to realize that he could shoot from a gondola mounted directly above the diamond—and did, to stirring effect. Using Life magazine's gargantuan 2000-millimeter lens in the late 1960s, he stationed himself in the center field bleachers to focus on where the pitch reached the catcher's mitt, a vantage point now standard for TV broadcasts. "Neil was the photojournalistic equivalent of Alfred Hitchcock, with shots like the overhead angle in Psycho ," says Gabriel Schechter, a writer who contributed to a new collection of Leifer's baseball pictures, Ballet in the Dirt: The Golden Age of Baseball .

Born in New York City in 1942 and raised on the Lower East Side of Manhattan, Leifer grew up watching ballgames with his father, Abraham, a postal worker, at the Polo Grounds (home of his father's beloved Giants) and Ebbets Field (home of the Dodgers). Leifer remembers taking a picture of Jackie Robinson on Camera Day at a Dodgers game when he was 13. The young photographer received training in technique at the Henry Street Settlement in New York and began selling photos as a teenager. At 18, he scored his first Sports Illustrated cover (of New York Giants quarterback Y. A. Tittle).

Leifer almost had to align the planets to get his double-play photograph at Dodgers Stadium, in Los Angeles, on April 25, 1965. He had brought his father to the game to watch the Dodgers take on the Philadelphia Phillies. "It was his first trip to the West Coast," Leifer says. "Dad hadn't yet gotten over the Dodgers and the Giants moving to California, but it was a thrill for him to be there anyway." Abraham Leifer was "handy at building stuff," so the photographer asked him to put together a small wooden box that could be put into a space carved out of the padding in the second base bag. Into the box went a Leica connected—through wires buried a few inches under the infield dirt—to a remote release behind first base. (Dodgers officials, Leifer says, were keen to cooperate with Sports Illustrated , and seemingly indifferent to any travails this imposed on the groundskeepers.) "I used a 21-millimeter lens"—a wide-angle lens—"because I wanted to get the stands as well as the play," Leifer recalls. "My father actually had the remote release, while I was shooting with another camera."

A classic double play developed in the third inning. With Willie Davis—the Dodgers' great center fielder and then the fastest man in baseball—on first, batter Tommy Davis poked the ball to the infield. With perfect timing, Leifer père hit the remote release and caught Willie Davis launching into his slide toward the fielder's foot.

"We got the shot," Leifer recalls. But Davis hit the bag so hard he knocked the Leica out of place, so "that picture was the only one we got." (For the record, the Phillies got the two outs, and eventually the win, 6-4.) The image went unpublished in Sports Illustrated —it "just didn't fit into a particular story," Leifer says—and so makes its print debut in Ballet in the Dirt .

Did Davis see the camera? "No, I couldn't pay attention to stuff like that," he says. "I put a notebook together of all the ways to slide, so when I slid into base, I put everything together in a split second. In my mind, it was as if I'd already done it before I did it." Davis, 68, retired from the majors in 1979 and lives in Burbank, California, near his old team's stadium.

Leifer shot for Sports Illustrated from 1960 until he left in 1978 to make his mark photographing everything from politics to wildlife for other titles in the Time-Life family. His dad died in 1982. By the time the younger Leifer left Time Inc. in 1990 (to concentrate on filmmaking, both documentaries and shorts), he had produced more than 200 covers for the company's magazines—and an archive that suggests nobody got inside baseball better than he did.

Owen Edwards is a frequent contributor to Smithsonian .

Post a Comment