Collaborations

Imagine a time when students in one of the poorest schools in Africa become scientists for a week by measuring the health of nearby forests and comparing their results with data collected by students and scientists around the world. Or when K-12 students at U.S. military bases in remote locations access the collections of the Smithsonian American Art Museum and learn about them from the museum‘s art educators. Actually, that day is here. Such programs are the vanguard of the Institution‘s approach to learning, which focuses on what Claudine Brown, our new assistant secretary for education and access, calls “action-based learning.” In tune with the popularity of digital devices, this form of learning builds on curiosity while emphasizing fundamentals, teamwork and communication.

Our partners in this work include the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, which recently provided $30 million to create the Youth Access Endowment; it will enable us to connect to a generation of Americans who might not be familiar with the Smithsonian, or who cannot afford to visit our museums in person. The U.S. Department of Education awarded $25.5 million to our National Science Resources Center (supplemented by more than $8 million raised by the center from private donors). This will further enrich our 20-plus years of implementing a comprehensive approach to transforming K-12 science education programs in more than 1,200 school districts in 48 states representing 30 percent of the U.S. student population (see nsrconlinerg ). In April 2010 the Pearson Foundation committed $2.2 million to support the use of mobile learning approaches. For example, last summer the National Postal Museum and the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden held 21 workshops for teachers and students. Participating teens learned how to curate their own exhibitions and produce videos and podcasts as they created theme-based scavenger hunts using mobile learning devices.

The Smithsonian has also joined Microsoft Partners in Learning and TakingITGlobal to create a program called Shout. It offers educators and students worldwide the ability to interact with each other and their communities, and online with top scientists and other experts to learn about and take action on environmental issues. One example of Shout is the forest-health measuring described above.

Another leading-edge digital collaboration is the Google Art Project, which lets online visitors stroll through the halls of the Freer Gallery of Art—using Google Street View technology—and examine artworks in brushstroke detail through gigapixel imaging.

For more information about the Institution‘s digital programs, visit smithsonianeducationrg . We invite you to join us in imagining a future where education is available to the world at the touch of a digital tablet—a future that excites new generations about learning and helping to solve global problems.

G. Wayne Clough is Secretary of the Smithsonian Institution.

Ned Kahn: The Limits of the Knowable

Last June, sculptor Ned Kahn’s 17-year-old son approached him with a box.

“I got you a traditional Father’s Day gift,” Ben Kahn warned his Dad. “But it’s not a traditional Father’s Day gift.“

Inside was a tie—made of polished, perforated aluminum. The gift was especially significant because Ben had fashioned it in the workshop of San Francisco’s Exploratorium: the legendary hands-on science museum where Ned had served as artist-in-residence for 14 years.

Even so, the tie seemed incongruous; a more appropriate gift might have been a silk-lined hard hat. Though Kahn appears pensive and soft-spoken, this large-scale environmental artist has won international acclaim by building tornadoes, orchestrating the wind and channeling ocean tides into explosive blowholes.

Kahn, a youthful 51, has a narrow face and dark eyes that often focus in the distance. He majored in botany and environmental science at the University of Connecticut, then worked at the Exploratorium from 1982 until 1996. Physicist Frank Oppenheimer, the museum’s brilliant and eccentric founder (and the younger brother of J. Robert Oppenheimer), became his mentor.

“Finally, I had someone I could ask all the questions that had been puzzling me for years. Like, ‘What’s actually flowing through a wire when you turn on the light?’ Frank loved questions like that,” recalls Kahn. “He would lead me through all the electricity exhibits in the museum, explaining them in detail. Then he’d end this long explanation by saying, ‘Basically, we don’t know what flows through a wire!’

“It was an awakening. It made me realize that what we do know of the world is based on our view through very small windows. The whole idea of limits—the limits of what’s really knowable—has been woven through everything I’ve done.”

Kahn’s interactive Tornado —an eight-foot-high fog twister that visitors can literally walk through without being carried away to Oz—is still one of the Exploratorium’s signature attractions. It’s a good example of what Kahn means when he refers to his pieces as “turbulent landscapes.” For nearly 30 years, he has been fascinated by the dynamic interplay of natural forces that operate, often invisibly, around us.

“I spent a year trying to make that first tornado sculpture work,” Kahn confesses with barely concealed amusement. “Sometimes I’d be there late at night. I’d aim the fans and the fog machine, and get it all fine-tuned. The thing would be working perfectly! Then I’d come back the next morning, and it wouldn’t work at all. I was going crazy.

“After months of this, I realized that it was all about the air currents in that old, drafty Exploratorium building. Which doors were open, or where the sun was heating the roof, affected everything. It slowly dawned on me, how intertwined the sculpture was with the building’s entire air system.

“This made me think: Where does an environmental sculpture begin, and where does it end? If my tornado was being affected by the air currents in the building, which were being affected by the wind outside the building, there never was a real border between the sculpture and the whole atmosphere of the Earth.”

* * *

Ned Kahn lives and works in Graton, a small town about 50 miles north of San Francisco. His studio is filled with motors, pipes, metalworking machinery and prototypes for kinetic sculptures. It looks like a salvage yard for spaceship parts.

His early works modeled on a Lilliputian scale the gigantic, always interactive forces of nature. Air columns filled with microscopic beads created patterns of ever-changing sand dunes; spinning glass orbs filled with a clever mix of colored liquid soaps appeared to contain the atmospheric storms seething across Neptune or Jupiter.

As he received more public art commissions, his works grew larger. New “tornadoes,” commissioned by science museums in the United States and Europe, added several stories in height. Whirlpools and blowholes were installed near city piers; the bare walls of buildings were surfaced with thousands of tiny hinged aluminum panels, animated by the ever-shifting patterns of the wind. In 2003 Kahn’s environmental art was recognized by the MacArthur Foundation, which awarded him a “genius” grant. Far from making him feel self-important, the honor has given him a droll perspective on the art world.

“It’s much easier to generate ideas than come up with something that really works,” Kahn observes, spinning a fluid-filled sphere called Turbulent Orb . “One of the dangerous things about becoming a MacArthur Fellow is that people start to take even your half-baked ideas seriously. It makes me nervous … because a lot of my ideas are bad!”

But a large percentage of his ideas are brilliant. Recently unveiled projects include the 20-foot diameter Avalanche at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, and the astounding Rain Oculus : a 70-foot-wide whirlpool at the Marina Bay Sands complex in Singapore (designed with architect Moshe Safdie). The huge whirlpool—which can circulate 6,000 gallons of water per minute—functions as a kinetic sculpture, a skylight (and waterfall) for the shopping arcade below, and part of the building’s rain-collecting system.

“I love working with Ned,” says Safdie. “His installations not only harness the forces of nature, but—more relevantly—teach us about them. Since my architecture is about working in harmony with nature, this is a perfect fit. I think we both come out feeling enriched, and that our own work is profoundly complemented by the other’s.”

Avalanche , meanwhile, is a movable wheel filled with a mixture of irregular garnet sand and tiny, spherical glass beads. Flowing together, they evoke the dynamics of moving soil, sand and snow. For this project Kahn consulted with University of Chicago physicist Sidney Nagel, who studies the behavior of water droplets, granular matter and other “disordered systems.”

“The enormous wheel is mesmerizing, as small avalanches build up and interact with one another,” Nagel observes. “Ned has the intuition and insight to see how something that starts out small and simple can take on layers of texture when it is enlarged. He captures the playfulness of the scientist in the lab—on our best days!—and translates the excitement of discovery so that it can be enjoyed by all.”

* * *

Kahn often works on dozens of projects simultaneously. At this writing they include everything from a Cloud Arbor (a mist sculpture for the Pittsburgh Children’s Museum) to an installation on the side of a giant parking garage in Brisbane, Australia. But he finds himself drawn increasingly to works that go beyond the purely aesthetic.

“I’ve been getting more excited about projects where what I’m doing is useful ; where the artwork actually has some benefit to the building,”

Solar panels, he believes, can be made far more attractive. “And wind turbines are a great interest of mine,” Kahn says. “There’s a lot of backlash against wind power; people think it’s ugly and noisy and kills birds. I think there’s a potential for me to help change people’s attitudes, and show that you can do it in beautiful ways.”

A current commission, for the new PUC building in San Francisco (in collaboration with KMD Architects), takes a revolutionary approach to wind power. When completed, a wide channel running up the side of the 12-story building will hold a tower of sculptural wind turbines, feeding electricity directly into the building’s power grid.

“How much? No one’s certain. Because what we’re doing—using the architecture as a wind funnel—is uncharted territory. Even the people who make the turbines are excited to see what they can do!”

Laced with thousands of tiny yellow-green lights, the facade of the building will flicker at night like a grid of fireflies, revealing otherwise invisible wind currents.

As the scale of his projects increase, his ideas become ever wilder. He’s currently researching how water droplets generate electrical charges, a process that produces famously dramatic results. “I’ve been working on designs for a fountain that will store and create electrical discharges,” he grins. “A sculpture that would produce real lightning.”

For an artist preparing to throw thunderbolts around, Ned Kahn remains remarkably unpretentious. This arises in part from his 30-plus years of morning vipassana (mindfulness) meditation, as well as the fact that he’s usually channeling forces much larger than himself.

“Most sculptures are a celebration of the skill of the artist,” he admits. “But in the things that I make—even though I’ve created the structure—it’s really not me that’s doing the sculpting. I’ve assembled the symphony, and the musicians, but something besides me is actually composing and recomposing the piece.”

To date, Ned Kahn has collaborated with more than 25 architecture and design companies around the world. With so much time scheduled on hard-hat construction sites, I can’t help but wonder when he’ll next put on that tie.

“Hopefully, never,” Kahn laughs. “I’m just not a tie guy. But it is a good conversation starter.”

How to Trademark a Fruit

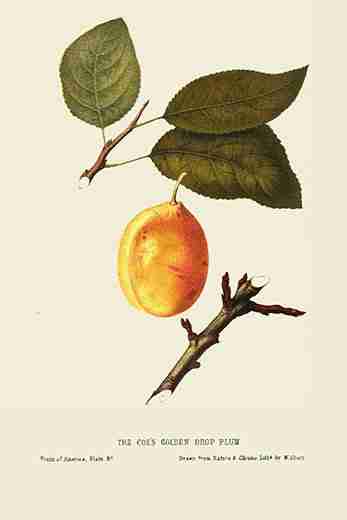

In 1847, Charles M. Hovey, a stalwart of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society and the proprietor of Hovey & Co., a 40-acre nursery in Cambridge, began publishing a series of handsomely illustrated prints of American fruits. Most of the trees—apple, pear, peach, plum and cherry—had come from England and Europe. Over time, many new fruit varieties emerged from natural cross-pollinations effected by wind, birds and insects—for example, the Jonathan apple, after Jonathan Hasbrouck, who found it growing on a farm in Kingston, New York. By the mid-19th century, a few new indigenous fruit varieties had arisen from breeding, notably Hovey’s own widely admired seedling strawberry and the prizewinning Concord grape, a recent backyard production of Ephraim Bull, a neighbor of Ralph Waldo Emerson.

At the time, regional and national agricultural markets were emerging, aided by steamboats, canals and railroads. The trend was accompanied by expansion in the number of commercial seed and nursery entrepreneurs. State horticultural societies dotted the land, and in 1848, several of their leaders in the Eastern states initiated what became the first national organization of fruit men—the American Pomological Society, its name drawn from Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruits. Marking these developments, in 1852 Hovey gathered his series of prints into a compendium called The Fruits of America, Volume 1 , declaring that he felt “a national pride” in portraying the “delicious fruits...in our own country, many of them surpassed by none of foreign growth,” thus demonstrating the developing “skill of our Pomologists” to the “cultivators of the world.” Further evidence of their skill came with publication of Volume 2 , in 1856.

I first came across Hovey’s book while researching the history of new varieties of plants and animals, and the protection of the intellectual property they entailed. In the mid-19th century, patent protection did not extend to living organisms as it does now, when they are not only patented but also precisely identifiable by their DNA. Still, fruit men in Hovey’s era were alive to the concept of “intellectual property.” Operating in increasingly competitive markets, they offered new fruits as often as possible, and if they were to protect their property, they had to identify it.

Hovey’s aims transcended celebration. He published the illustrations so the fruits could be reliably identified by growers as well as sellers, and especially by the innovators who first brought them out. I discovered upon further digging—in nursery catalogs, handbooks and advertisements—that his effort exemplified the beginnings of a small industry of fruit illustration that was an integral part of the pomological trade in the latter half of the 19th century. And much of it, while produced for commercial purposes, was aesthetically arresting. Indeed, it combined traditional techniques and new technology, leaving us a large, often exquisite body of American botanical art.

The need for pictures was prompted by the proliferation of fruit names that accompanied the multiplication of varieties. Fruits in the United States were bought and sold under a riot of synonyms, creating, Hovey noted, “a confusion of nomenclature which has greatly retarded the general cultivation of the newer and more valuable varieties.” One popular apple, the Ben Davis, was also called Kentucky Streak, Carolina Red Streak, New York Pippin, Red Pippin, Victoria Red and Carolina Red. William Howsley, a compiler of apple synonyms, called the tendency of “so many old and fine varieties” to be cited in horticultural publications under new names “an intolerable evil, and grievous to be borne.”

Variant nomenclature had long plagued botany. Why now such passionate objections to the proliferation of synonyms, to a mere confusion of names? A major reason was that the practice lent itself to misrepresentation and fraud. Whatever their origins—hybrids, chance finds or imports—improved fruits usually required effort and investment to turn them into marketable products. Unprotected by patents on their productions, fruit innovators could be ripped off in several ways.

In the rapidly expanding nursery industry, a good deal of seedling stock was sold by small nurseries and tree peddlers, who could obtain cheap, undistinguished stock, then tell buyers it was the product of a reliable firm or promote it as a prized variety. Buyers would be none the wiser: a tree’s identity often did not become manifest until several years after planting.

Fruit innovators also suffered from the kind of appropriation faced by today’s originators of digitized music and film. Fruit trees and vines can be reproduced identically through asexual reproduction by grafting scions onto root stock, or by rooting cuttings directly into soil. Competitors could—and did—purchase valuable trees, or take cuttings from a nursery in the dead of night, then propagate and sell the trees, usually under the original name. A good apple by any other name would taste as sweet.

Nurserymen like Hovey founded the American Pomological Society in no small part to provide a reliable body of information about the provenance, characteristics and, especially, names of fruits. The society promptly established a Committee on Synonyms and a Catalogue, hopeful, as its president said, that an authoritative voice would be “the best means of preventing those numerous impositions and frauds which, we regret to say, have been practiced upon our fellow citizens, by adventurous speculators or ignorant and unscrupulous venders.”

Yet the society had no police power over names, and its verbal descriptions were often so inexact as to be of little use. It characterized the “Autumn Seek-No-Further” apple as “a fine fruit, above medium size; greenish white, splashed with carmine. Very good.”

Drawings and paintings had long been used to identify botanical specimens, including fruits. During the early 19th century in Britain and France, heightened attention was given to the practice of illustration in response to the proliferation of different names for the same fruits. An exquisite exemplar of the genre was the artist William Hooker’s Pomona Londinensis , the first volume of which was published in London in 1818. But beautiful as they were, pictorial renditions such as Hooker’s did not lend themselves to the widespread identification of fruits, even in small markets, let alone the steadily enlarging ones of the United States. Hooker’s illustrations were hand-painted. Such paintings, or watercolored lithographs or etchings, were laborious and expensive to produce and limited in number.

But in the late 1830s, William Sharp, an English painter, drawing teacher and lithographer, immigrated to Boston with a printing technology that had been devised in Europe. It promised to enable the production of multiple-colored pictures. Called chromolithography, it involved impressing different colors on the same drawing in as many as 15 successive printings.

Charles Hovey enlisted Sharp to produce the colored plates in Fruits of America , declaring that his “principal object” in publishing the work was to “reduce the chaos of names to something like order.” Together, the two volumes included 96 colored plates, each handsomely depicting a different fruit with its stem and leaves. Hovey held that Sharp’s plates showed that the “art of chromo-lithography produces a far more beautiful and correct representation than that of the ordinary lithograph, washed in color, in the usual way. Indeed, the plates have the richness of actual paintings, which could not be executed for ten times the value of a single copy.”

Not everyone agreed. One critic said that fruit chromolithographs lacked “that fidelity to nature, and delicacy of tint, which characterize the best English and French coloured plates, done by hand.” Some of the illustrations did appear metallic in tone or fuzzy, which was hardly surprising. Chromolithography was a complex, demanding process, an art in and of itself. It required a sophisticated understanding of color, the inventive use of inks and perfect registration of the stone with the print in each successive impression.

The editors of the Transactions of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society , who had tried chromolithographs and been disappointed, resorted to a prior technique—black-and-white lithographs that were then watercolored by hand. The editors engaged an artist named Joseph Prestele, a German immigrant from Bavaria who had been a staff artist at the Royal Botanical Garden in Munich. He had been making a name for himself in the United States as a botanical illustrator of great clarity, accuracy and minuteness of detail. Prestele produced four plates for the 1848 volume of the Transactions , and observers greeted his efforts with enthusiasm, celebrating them as far superior to Sharp’s chromolithographs.

Artists like Prestele did well in the commercial sector among nurserymen eager to advertise their fruit varieties, original or otherwise. But it was only the large firms that could afford to regularly publish catalogs with hand-colored plates.

The smaller firms, which were legion, relied on peddler’s handbooks such as The Colored Fruit Book for the Use of Nurserymen , published in 1859 by Dellon Marcus Dewey, of Rochester, New York. It included 70 colored prints, which Dewey advertised had been meticulously drawn and colored from nature, saying their purpose was to “place before the purchaser of Fruit Trees, as faithful a representation of the Fruit as is possible to make, by the process adopted.” Deluxe editions of Dewey’s plate books, edged in gilt and bound in morocco leather, served as prizes at horticultural fairs and as parlor table books. Dewey produced the books in quantity by employing some 30 people, including several capable German, English and American artists. He also published the Tree Agents’ Private Guide , which advised salesmen to impress customers that they were God-fearing, upright and moral.

Still, colored illustrations could not by themselves protect an innovator’s intellectual property. Luther Burbank, the famed creator of fruits in Santa Rosa, California, fulminated that he had “been robbed and swindled out of my best work by name thieves, plant thieves and in various ways too well known to the originator.”

What to do? In 1891 some fruit men called for the creation of a national register of plants under the Department of Agriculture. The originator would send the department a sample, a description and perhaps an illustration of his innovation, and the department would issue a certificate, a type of trademark ensuring him inviolable rights in his creation. No such formal registration system was established, but a de facto version had been created in 1886, when the agency organized a division of pomology. It established a catalog of fruits and attempted to deal with the problem of nomenclature by hiring artists to paint watercolor illustrations of novel fruits received from around the country. The first such artist was William H. Prestele, one of Joseph Prestele’s sons. He produced paintings marked by naturalness and grace as well as by painstaking attention to botanical detail, usually including the interior of the fruit and its twigs and leaves.

By the late 1930s, when the illustration program ended, the division had employed or used some 65 artists, at least 22 of whom were women. They produced some 7,700 watercolors of diverse fruits, including apples, blackberries and raspberries, currants and gooseberries, pears, quince, citrus, peaches, plums and strawberries.

Yet neither the registration scheme nor any other method protected the fruit men’s rights as originators. Then, in 1930, after years of their lobbying, Congress passed the Plant Patent Act. The act authorized a patent to anyone who “has invented or discovered and asexually reproduced any distinct and new variety of plant.” It covered most fruit trees and vines as well as clonable flowers such as roses. It excluded tuber-propagated plants such as potatoes, probably to satisfy objections to patenting a staple of the American diet.

The act, the first statute anywhere that extended patent coverage to living organisms, laid the foundation for the extension, a half century later, of intellectual property protection to all organisms other than ourselves. But if it anticipated the future, the act also paid homage to the past by requiring would-be plant patentees, like other applicants, to submit drawings of their products. Law thus became a stimulus to art, closing the circle between colored illustrations of fruits and the intellectual property they embodied.

Daniel J. Kevles , a historian at Yale University, is writing a book about intellectual property and living things.

Post a Comment