Stolen: How the Mona Lisa Became the World’s Most Famous Painting

It was a quiet, humid Monday morning in Paris, 21 August 1911. Three men were hurrying out of the Louvre. It was odd, since the museum was closed to visitors on Mondays, and odder still with what one of them had under his jacket.

They were Vincenzo Perugia and the brothers Lancelotti, Vincenzo and Michele, young Italian handymen. They had come to the Louvre on Sunday afternoon and secreted themselves overnight in a narrow storeroom near the Salon Carré, a gallery stuffed with Renaissance paintings. In the morning, wearing white workmen’s smocks, they had gone into the Salon Carré. They seized a small painting off the wall. Quickly, they ripped off its glass shadow box and frame and Perugia hid it under his clothes. They slipped out of the gallery, down a back stairwell and through a side entrance and into the streets of Paris.

They had stolen the Mona Lisa .

It would be 26 hours before someone noticed that the painting was missing. It was understandable. At the time the Louvre was the largest building in the world, with more than 1,000 rooms spread over 45 acres. Security was weak; fewer than 150 guards protected the quarter-of-a-million objects. Statues disappeared, paintings got damaged. (A heavy statue of the Egyptian god Isis was stolen about a year before the Mona Lisa and in 1907, a woman was sentenced to six months in prison for slashing Jean Auguste Ingres' Pius VII in the Sistine Chapel .)

At the time of the “Mona Lisa” heist, Leonardo da Vinci's masterpiece was far from the most visited item in the museum. Leonardo painted the portrait around 1507, and it was not until the 1860s that art critics claimed the Mona Lisa was one of the finest examples of Renaissance painting. This judgment, however, had not yet filtered beyond a thin slice of the intelligentsia, and interest in it was relatively minimal. In his 1878 guidebook to Paris, travel writer Karl Baedeker offered a paragraph of description about the portrait; in 1907 he had a mere two sentences, much less than the other gems in the museum, such as Nike of Samothrace and Venus de Milo .

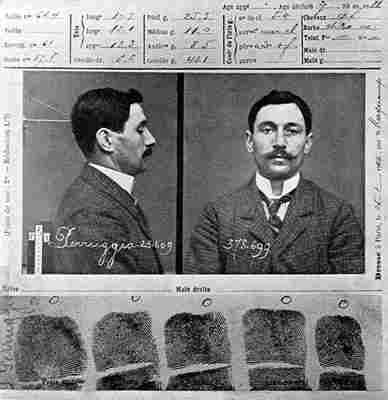

Which isn’t to say it was obscure. A letter mailed to the Louvre in 1910 from Vienna had threatened the Mona Lisa so museum officials hired the glazier firm Cobier to put a dozen of its more prized paintings under glass. The work took three months; one of the Cobier men assigned to the project was Vincenzo Perugia. The son of a bricklayer, Perugia grew up in Dumenza, a Lombardy village north of Milan. In 1907 at the age of 25, Vincenzo left home, trying out Paris, Milan and then Lyon. After a year, he settled in Paris with his two brothers in the Italian enclave in the 10th Arrondissement.

Perugia was short, just 5 feet 3, and quick to challenge any insult, to himself or his nation. His brothers called him a passoide o megloi , a nut or madman. His fellow French construction workers, Perugia later testified in court, “almost always called me ‘ mangia maccheroni ’ [macaroni eater] and very often they stole my personal property and salted my wine.”

Twice the Parisian police arrested Perugia. In June 1908 he spent a night in jail for attempting to rob a prostitute. Eight months later, he clocked in a week in the Macon, the notorious Parisian prison and paid a 16-franc fine for carrying a gun during a fistfight. He even quarreled with his future co-conspirators; he once stopped speaking to Vincenzo Lancelotti over a disputed 1-franc loan.

Perugia wanted to be more than a construction worker. Appearing in court in 1914 for the theft of the Mona Lisa , he was called a housepainter by the prosecution. Perugia stood up and declared himself a pittore , an artist. He had taught himself how to read and sometimes holed himself up in coffeehouses or museums, poring through books and newspapers.

Stealing the Mona Lisa made sense. Most purloined paintings that were not immediately held for ransom didn't go to a wealthy aristocrat’s secret hideaway, but instead slide into an illicit pipeline being used as barter or collateral for drugs, arms and other stolen goods. Perugia had enough connections to criminal circles that he hoped to barter or sell it.

Unfortunately for Perugia, the Mona Lisa got too hot to hock. Initially, the afternoon newspapers in Paris had nothing on Monday, and the following morning’s papers were also curiously quiet on the matter. Would the Louvre cover it up, pretend it had not happened?

Finally, late on Tuesday, there was a media explosion when the Louvre issued a statement announcing the theft. Newspapers around the world came out with banner headlines. Wanted posters for the painting appeared on Parisian walls. Crowds massed at police headquarters. Thousands of spectators, including Franz Kafka, flooded into the Salon Carré when the Louvre reopened after a week to stare at the empty wall with its four lonely iron hooks. Kafka and his traveling companion Max Brod marveled at the “mark of shame” at the Louvre and attended a vaudeville show lampooning the theft.

Satirical postcards, a short film and cabaret songs followed—popular culture seized upon the theft and turned high art into mass art. Perugia realized that he had not pinched an old Italian painting from a decaying royal palace. He had unluckily stolen what had become, in a few short days, the world's most famous painting.

Perugia squirreled the Mona Lisa away in the false bottom of a wooden trunk in his room at his boardinghouse. When the Parisian police interrogated him in November 1911 as a part of their interviews of all Louvre employees, he blithely said he only learned of the theft from the newspapers and that the reason he was late to work that Monday in August—as his employer had told the police—was that he had drunk too much the night before and overslept.

The police bought the story. Supremely inept, they ignored Perugia and instead arrested the artist Pablo Picasso and the poet and critic Guillaume Apollinaire. (They were friends with a thief who admitted to pinching little sculptures from the Louvre.) The two were promptly released.

In December 1913, after 28 months, Perugia left his Parisian boardinghouse with his trunk and took a train to Florence where he tried to offload the painting on an art dealer who promptly called the police. Perugia was arrested. After a brief trial in Florence, he pleaded guilty and served only eight months in prison.

Thanks to the high-profile heist, the Mona Lisa was now a global icon. Under a shower of even more publicity, it returned to the Louvre following mobbed exhibitions in Florence, Milan and Rome. In the first two days after it was rehung in the Salon Carré, more than 100,000 people viewed it. Today, eight million people see the Mona Lisa every year.

As soon as the painting was stolen in 1911, conspiracy theories sprouted up. Was it a hoax? Some said the theft was the French government’s way of trying to distract public opinion from uprisings in colonial West Africa. A few months before the painting was found, the New York Times speculated that Louvre restorers had botched a restoration job of the Mona Lisa ; to cover this up, the museum concocted the story of an outlandish theft.

Even after the recovery of the Mona Lisa , the world was still incredulous. How could a few Italian carpenters have pulled this caper off by themselves? For years, rumors surfaced that a gang of international art thieves had poached the painting and substituted a fake that was in Perugia's possession when he was caught in Florence. In a 1932 issue of The Saturday Evening Post , Karl Decker, an American journalist, offered a twist: a shady Argentine swindler had arranged for six copies of the Mona Lisa to be made and sold after Perugia’s theft (each buyer thought he had the original).

Two English-language nonfiction accounts of the theft, a 1981 book by Seymour Reit and a 2009 retelling by R.A. Scotti, carry Decker’s story to the hilt, even though there is no supporting historical evidence.

A century has passed since Perugia pinched the painting, and yet historians are still reluctant to give him the credit as the unwitting catalyst for making the Mona Lisa the world-famous icon that it is today.

William Eggleston’s Big Wheels

Although a photograph always shows the same things, that doesn’t mean those things are always seen the same. This William Eggleston picture is variously known as Untitled, Tricycle and Memphis, 1970 . It has been variously seen, too. Now considered a classic, it was initially greeted in many quarters with incomprehension, even as an outright affront.

Eggleston’s tricycle first attracted attention as part of a 1976 exhibition of his work at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City. It appeared, in fact, on the cover of the exhibition catalog, William Eggleston’s Guide . “The most hated show of the year,” one critic wrote. “Guide to what?” detractors sniffed about a show whose photographic subjects also included a tiled bathroom wall, the interior of a kitchen stove and the contents of a freezer. Hilton Kramer called Eggleston’s images “perfectly banal” and “perfectly boring.” Kramer, the New York Times’ chief art critic, was playing off of John Szarkowski, MoMA’s director of photography, who had described Eggleston’s photographs as “perfect.” Instead of perfection, Kramer saw “dismal figures inhabiting a commonplace world of little visual interest.”

How well do those words apply to Eggleston’s tricycle? “Dismal” is a subjective judgment. “Commonplace?” Yes, and proudly so. “Of little visual interest”? Well, that’s another story. For starters, Eggleston’s photograph represents a tectonic shift in the medium’s history: the growing acceptance of color in art photography. Tellingly, the MoMA show was the first major solo all-color photography exhibition in the museum’s history. Eggleston was the most prominent member of a cadre of young, talented photographers working in color: Stephen Shore, Joel Meyerowitz, Joel Sternfeld and Eggleston’s fellow Southerner William Christenberry. It was one thing to use color on a fashion model or a sunset. But a tricycle ?

Eggleston’s photograph also can be seen in larger cultural terms. In its small way, it’s an example of the growing prominence of white Southern culture in the ’70s—from Richard Nixon’s Southern strategy to the popularity of rock bands like the Allman Brothers and Lynyrd Skynyrd to the election of Jimmy Carter in the same year as the MoMA show. Then there’s a further, literary dimension. As the curator Walter Hopps wrote in an essay for a book following Eggleston’s 1998 Hasselblad Award, his “photographs carry the enriched reverberations of fiction.” This rather forlorn-looking child’s toy (notice the rusted handlebars) is a visual correlative for the ways banality was being used in the short stories of such contemporary writers as Ann Beattie and, especially, Raymond Carver.

Yet the best argument for the tricycle’s visual interest isn’t its place in photographic history or its Southern prov-enance or its affinity with literary “dirty realism.” It’s the photograph itself.

Homely objects had a long tradition of being photographed—but they were finely wrought homely objects, as in the portfolio of hand tools Walker Evans made for Fortune magazine in 1955. Eggleston’s tricycle is different. It’s at once beneath homeliness yet oddly exalted. One way Eggleston achieves this effect is obvious: he shoots the tricycle from a low angle. It looms large in the imagination because it looms large, period. Looking heavenward, Eggleston’s camera bestows on that tricycle the majesty—and ineffability—of an archangel’s throne.

The tricycle does not stand alone. You also find two ranch houses and a car in a carport. You have a patch of dead grass, some asphalt, the sweep of gray sky. The scene is all very, well, negligible . Or is it? The grass and asphalt almost eerily mirror the sky as neutral space. The trike is shot in such a way as to dominate the foreground, like a chariot of very youthful gods. Archangels, deities: for Eggleston, the profane is what’s sacred. Has anyone ever evoked the enchantment of the banal quite so well? “I am at war with the obvious,” he has said.

The tricycle’s many curves mock the angularity of the roofs to the rear. Then there’s the chromatic play of red handle grips with bluish-green seat and frame, not forgetting the several bits of white on seat, frame, stem and wheel rims—the whiteness playing off the roofs and trim of the houses. Color is absolutely not an afterthought. Eggleston started out as a black-and-white photographer—a good one, too, inspired in part by Henri Cartier-Bresson. The point is, Eggleston embraced color photography consciously, aware of how much a richer palette would bring to his art. Remove color, and you severely diminish the effect. The whole thing is a model of unobtrusive artistry amid the everyday nondescript. It seems so simple and artless. Looked at closely, though, it’s as cunning as a seduction, as ordered as a sonnet.

How to account for such a miracle of seeing and recording? Eggleston, now 72, has long declined to discuss the whys and wherefores of specific photographs. Reiner Holzemer’s 2008 documentary film, William Eggleston: Photographer , includes a black-and-white family snapshot. It shows a very young Eggleston in the foreground, looking natty in cap and sailor suit, a tricycle behind him. Might it be a sidewalk-worthy equivalent of Charles Foster Kane’s Rosebud? Surely, not even Eggleston can say. In such indeterminacy begins the mystery and wonder of art, three-wheeled and otherwise.

Mark Feeney , a Boston Globe writer, won a Pulitzer Prize for criticism in 2008.

Holding on to Gullah Culture

If a slave died while cutting rice stalks in the wet paddy fields on Sapelo Island, Georgia, those laboring with him were not permitted to attend to the body. The buzzards arrived first.

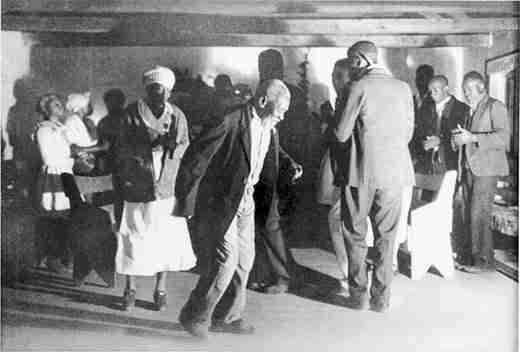

But at night, the deceased’s companions would gather to mourn. Dancing to the steady beat of a broom or stick, a circle of men would form around a leader—the “buzzard”— whose hands depicted the motion of the bird’s wings. He would rock closer and closer to the ground, nose first, to pick up a kerchief, symbolizing the body’s remains.

Cornelia Bailey, 65, is one of a handful of people still living on the 16,000-acre barrier island along Georgia’s Sea Coast. She remembers the “buzzard lope,” as the ritual was called. Growing up, she says, “you didn’t learn your history. You lived it.”

African-American linguist Lorenzo Dow Turner (1890-1972) was also privy to that history. In 1933, he conducted a series of interviews with Sea Coast residents—recorded on a bulky device powered by the truck engine of Bailey’s father-in-law. Thus he introduced the world to a community, known as Gullah or Geechee, that still retains music and dances from West Africa. Turner also studied the islanders’ unique dialect, which outsiders had long dismissed as poor English. But Turner’s research, published in 1949, demonstrated that the dialect was complex, comprising about 3,800 words and derived from 31 African languages.

Turner’s pioneering work, which academics credit for introducing African-American studies to U.S. curricula, is the subject of “Word, Shout, Song: Lorenzo Dow Turner Connecting Communities Through Language” at Smithsonian’s Anacostia Community Museum through July 24. Exhibit curator Alcione Amos says the Washington, D.C. museum acquired many of Turner’s original notes, pictures and recordings from his widow, Lois Turner Williams, in 2003. But Amos knew if she wanted to supplement Turner’s work, she would have to act quickly.

Today, only 55 Sapelo natives, ages 3 to 89, live in the island’s lone village, Hogg Hummock. “I wake up in the morning and count heads, to make sure nobody died overnight,” Bailey says.

“I knew there wasn’t much more time before the people who recognize the people in these photographs, and remember the culture they represented, are gone, too,” Amos says.

So she retraced Turner’s steps, traveling across the island conducting interviews. Sitting in Bailey’s kitchen, Amos played recordings on a laptop. A man’s voice sounds faded and cracked beneath the steady hum of the truck generator.

“That’s Uncle Shad, all right,” Bailey says, straining to hear his words. “Sure is.”

Bailey and Nettye Evans, 72, a childhood friend, identified four pictures in Amos’ collection. “I think that might be your husband’s great-grandmother, Katie Brown,” Evans says, pointing to a picture of a proud-looking woman wearing mostly white.

Bailey drove Amos around the island in a boxy utility van, pointing out houses and fields and slipping into island dialect: binya is a native islander, comya is a visitor.

In the back seat, Bailey’s grandson, 4-year-old Marcus, played with plastic toy trucks. He doesn’t use those words. And while he knows some traditional songs and dances, Marcus will likely follow the path of Sapelo’s three most recent graduates, who attended high school on the mainland and went on to college, with no plans to return. “My daughters would love to live here. Their heart is in Sapelo,” says Ben Hall, 75, whose father owned the island’s general store until it closed decades ago from lack of business. “But they can’t. There’s nothing for them.”

The Sapelo Island Culture and Revitalization Society is working to build a Geechee Gullah Cultural Interpretative Village—an interactive tourist attraction recreating different time periods of island life. It would bring jobs and generate revenue, Bailey says. The society, however, needs $1.6 million to move forward with the project.

Meanwhile, at the museum, Uncle Shad’s voice, now identified, relates the island’s history. The culture is too strong to ever die out completely, Bailey says. “You’ve got to have hope there’ll always be somebody here.”

Post a Comment