Day of the Iguanas

In the early 1920s, Diego Rivera returned to Mexico City from a trip to Oaxaca and began telling friends about a place where strong, beautiful women ruled. Soon Rivera was painting such women, and within a decade, the list of artists and intellectuals that followed the road south to Oaxaca included Frida Kahlo, Sergei Eisenstein and Langston Hughes. Photographers came too: Henri Cartier-Bresson, Tina Modotti, Edward Weston. To varying degrees, they were all taken with the indigenous Zapotec women on the Isthmus of Tehuantepec and the culture in which they really did enjoy more power and freedom than other women in Mexico.

Graciela Iturbide didn't travel to the region until 1979, but the photographs she made there have proved to be some of the most enduring images of Zapotec life. And her portrait of a woman named Zobeida—titled Nuestra Señora de las Iguanas (Our Lady of the Iguanas) and included in Graciela Iturbide: Juchitán , a recent collection of Iturbide's work—has practically become a symbol of Zapotec womanhood.

By the time Iturbide made her trip to the isthmus city of Juchitán, she had already shed several skins. Married at 20, a mother of three by 23, she seemed set for a traditional life as an upper-class wife in Mexico City. But her 6-year-old daughter died from an illness in 1970, and later Iturbide and her husband divorced. Although she had been studying filmmaking, Iturbide signed up for a still photography class taught by the Mexican master Manuel Alvarez Bravo. She was one of only a few students to enroll, and the class developed into an apprenticeship.

Iturbide had begun photographing in Mexico City and among the Seri Indians in the Sonora Desert when, in 1979, she was invited to take pictures in Juchitán by the artist Francisco Toledo, a native son and an advocate for the region's arts and culture. Iturbide spent a few days observing the Zapotec women, who seemed to project an almost ethereal self-possession—independent, at ease with their bodies and comfortable with their power, which came from control of the purse. "The men work" on farms and in factories, Iturbide says, "but they give money to the women."

The women also ruled the marketplace, where they sold textiles, tomatoes, fish, bread—"everything," Iturbide says, "all of it carried on their heads." It was amid the market's tumult one morning that she spotted Zobeida (whose name has also been given, incorrectly, as Zoraida). "Here she comes with the iguanas on her head! I could not believe it," Iturbide says. As Zobeida got ready to sell the lizards (as food), the photographer says, "she put the iguanas on the ground and I said: 'One moment, please. One moment! Please put the iguanas back!'"

Zobeida obliged; Iturbide raised her camera. "I had a Rolleiflex; only 12 frames and in this moment," she says. "I didn't know if it was OK or not."

It was more than OK. A year or so later, Iturbide presented several of her Juchitán photographs to Toledo, to be shown in a cultural center he had founded in the city. Somewhat to her surprise, Our Lady of the Iguanas —which she considered as but one image among many—was a hit. Residents asked for copies of it, and they put it on a banner. "The image is a very important one to the people of Juchitán," Iturbide says. "I don't know why. Many people have the poster in their house. Toledo made a postcard." The locals renamed the image "The Juchitán Medusa." "There are many legends about the iguanas and other animals, and maybe that image relates," Iturbide says. " Maybe ."

Although Iturbide returned to Juchitán many times for the better part of a decade, she also traveled widely, photographing in Africa, India and the American South. To her surprise, the Juchitán Medusa also traveled—turning up as an element in a Los Angeles mural, for example, and in the 1996 American feature film Female Perversions (starring Tilda Swinton as an ambitious, conflicted lawyer). When Iturbide went to Japan for an exhibition of her work, the curator told her he was glad she didn't bring her iguanas, says Rose Shoshana, founder of the Rose Gallery in Santa Monica, California, which represents Iturbide.

Ultimately, the pictures the photographer made in Juchitán were important to both her work and her reputation, says Judith Keller, who curated a recent Iturbide retrospective at the Getty Center in Los Angeles. "It reinforced her concern about the lives of women, and it validated her thinking that this is an important topic and this is something she should continue with," Keller says. In October, Iturbide will be awarded the Hasselblad Foundation International Award.

As for the Lady of the Iguanas herself, Zobeida died in 2004, but not before the image made her something of a celebrity. As anthropologists debated the exact nature of Juchitán society (matriarchal? matrifocal?), journalists would seek her out to ask, inevitably, if she was a feminist. Iturbide says Zobeida would answer: "'Yes. When my husband died, I work. I take care of myself.'"

Lynell George writes about arts and culture for the Los Angeles Times .

The Woman Behind Miss Piggy

Bonnie Erickson designed and built the inimitable Miss Piggy in 1974 for an early "Muppets" television special, produced by Jim Henson. Puppets, props and storyboards from Henson's prolific career are featured in the traveling exhibit "Jim Henson's Fantastic World." Anika Gupta spoke with Erickson.

You've been designing muppets and mascots for years. What attracts you to them? The creation of worlds—the whole process of designing characters, putting together a back story, giving the characters an environment in which they can thrive and casting performers who can bring them to life.

Why do puppets appeal to adults as well as children? They've been a tradition across the world for thousands of years as a form of storytelling. But, until recently, they have't been appreciated in the United States. Now, however, puppetry is finding a niche in the arts—dance, theater and even opera. I think people appreciate the performers' skill as well as the artistry of the puppets themselves. We owe a lot of that to [Muppets creator] Jim Henson's vision.

Who inspired the character of Miss Piggy? My mother used to live in North Dakota where Peggy Lee sang on the local radio station before she became a famous jazz singer. When I first created Miss Piggy I called her Miss Piggy Lee—as both a joke and an homage. Peggy Lee was a very independent woman, and Piggy certainly is the same. But as Piggy's fame began to grow, nobody wanted to upset Peggy Lee, especially because we admired her work. So, the Muppet's name was shortened to Miss Piggy.

Of all the characters you've designed, which are among your favorites? Statler and Waldorf, the two old men who heckled from the balcony in the Muppet Show. I could picture them in the Yale Club sipping brandy, surrounded by portraits of their predecessors. Another was Zoot, the blue-haired, balding saxophonist for the Muppet band "Electric Mayhem." He was fashioned after musician Gato Barbieri, based on a quick sketch I made when I saw him perform at a jazz club.

Let's say you get a contract to make a character. How does your creative process work? Well let me take the Philly Phanatic as an example. The managers approached us to design a mascot who could encourage fans to bring their families to the games. So we had to design a character who was child-friendly, who was playful and a little irreverent but not too silly. We'd heard from the Phillies that their crowd had booed the Easter bunny, so it was a challenge to come up with something that was not going to talk down to their audience. We wanted a character who had a life and a story. A lot of our characters are still performing today. We created Youppi for the Montreal Expos, and when the team moved out of Montreal Youppi was left without a home. So he was taken in by the hockey team. In my mind I've always thought of these characters as having a life, so they're free agents in many ways. When they lose a team, they go out and try to find another job.

What does it take for a character to become a legend, as happened with Miss Piggy and the Phanatic? Well, there are three factors. First, you need a good designer and a good concept. And in the case of puppeteers you need a really good performer. And then the client has to be very thoughtful and use the character well. When you put all these pieces together you have at least a shot at creating a character people will be drawn to.

Spirit of the Sea

On the morning of June 19, a crowd gathered in Washington, D.C. to watch a boat plying the Potomac. The distinctively carved canoe bulged with eight paddlers sitting two abreast, while a coxswain beat a drum to keep stroke. "Who are you, and what are you doing here?" shouted a man on shore as the boat began to dock. "We are the Tlingit, Haida and Tsimshian," a paddler responded, reciting the names of Northwest Coast Indian tribes.

Its maiden voyage complete, the 26-foot dugout canoe, named the Yéil Yeik (Raven Spirit), is now suspended from the ceiling in the Sant Ocean Hall, which opens September 27 at the Natural History Museum. "Human life on earth has in many ways been a response to the challenges of the ocean world," says anthropologist and curator Stephen Loring. The canoe is a "uniquely American watercraft and a powerful symbol of human ingenuity and accomplishment."

For the Northwest Coast Indians—who inhabit the offshore islands and jagged coastline extending from the Oregon-Washington border to Yakutat Bay in the southeastern Alaskan panhandle—the canoe enabled them to avoid geographic isolation. "Our people couldn't be who we are and where we are without the canoe," says Tlinglit elder Clarence Jackson. Indeed, archaeological findings suggest a complex maritime culture at least 10,000 years old.

The Tlingit learned to subsist on the ocean. "When the tide goes out, our table is set" is a common refrain. But despite this intimate connection with the sea, canoe-building fell into decline during the past century. "Everybody had a knack for hewing out a canoe," says Jackson, of the pre-1920 era. Motorboats have since replaced traditional canoes.

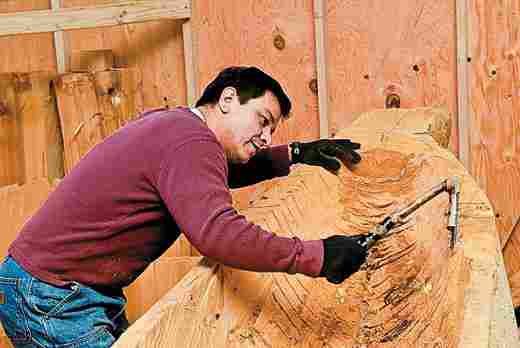

But a few Tlingit artisans, such as Doug Chilton, have sparked a revival. The Native-owned Sealaska Corporation donated a 350-year-old red cedar tree to the Raven Spirit project. Traditionally, carvers would dig a trough down the center of the canoe, light a fire, let it burn awhile and then knock out the charred areas with an ax. To ease their labors, Chilton and his fellow artisans, including his brother Brian, used chain saws. Once hewed, the canoe was steamed, in the manner used by their ancestors, to expand the sides and curve up the ends.

As a finishing touch, they mounted a figurehead of a raven with a copper sun in its beak—to represent the Tlingit legend of the raven bringing light to the world. As if to remind those involved of the spirits at work in the project, a raven, distinguished by a broken wing that forced its feathers to stick straight out, visited Chilton several times while he was working.

"He was almost claiming ownership of the canoe," says Chilton. To honor the wounded raven, Chilton whittled its tousled wing into the figurehead. "The spirit of that raven was there in that canoe."

Post a Comment