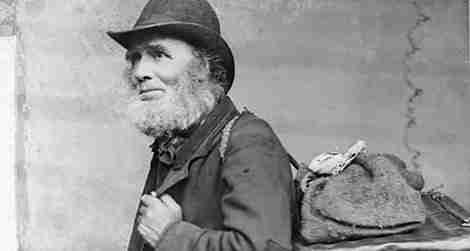

The Last of the Cornish Packmen

Before the coming of the railways, and the buses, and the motor car, when it was not uncommon for isolated farms to be a day’s walk from the nearest shops, the closest many people got to a department store was when a wandering peddler came to call.

Wheeled transport was still expensive then, and most rural roads remained unmade, so the great majority of these traveling salesmen carried their goods on their backs. Their packs usually weighed about a hundredweight (100 pounds, or about 50 kilos—not much less than their owners), and they concealed a treasure trove of bits and pieces, everything from household goods to horsehair wigs, all neatly arranged in drawers. Since the customers were practically all female, the best-sellers were almost always beauty products; readers of Anne of Green Gables may recall that she procured the dye that colored her hair green from just such a peddler.

Over the years, these fixtures of the rural scene went by many names; they were buffers, or duffers, or packmen, or dustyfoots. Some were crooks, but a surprisingly high proportion of them were honest tradesmen, more or less, for it was not possible to built a profitable round without providing customers with a reasonable service. By the middle of the nineteenth century, it has been estimated, an honest packman on the roads of England might earn more than a pound a week, a pretty decent income at that time.

For several hundred years, the packman was a welcome sight to many customers. “He was the one great thrill in the lives of the girls and women,” the writer H.V. Morton tells us, “whose eyes sparkled as he pulled out his trays and offered to their vanity cloths and trifles from the distant town.” Indeed, “the inmates of the farm-house where they locate for the night consider themselves fortunate in having to entertain the packman; for he is their newsmonger, their story-teller and their friend.”

I’m interested here, though, in chronicling the decline and fall of this age-old way of life—for the packman could not survive the coming of the modern world, of course. Exactly when the species became doomed is still debated; in Britain, historians may point to the year 1810, when it became law for peddlers to purchase a pricey annual license in order to carry on their trade. There’s evidence, however, that the packmen prospered for at least a little longer than that; census statistics suggest that the really precipitous decline in their numbers, in England at least, dates to between 1841 and 1851, when the total plunged from more than 17,000 to a mere 2,500, a fall of more than 85 percent. Henry Mayhew, whose lively survey London Labour and the London Poor is our greatest storehouse of information on marginal lives in the Victorian age, noted in 1851 that “the system does not prevail to so great an extent as it did some years back.” Mayhew found that there were then only five packmen and a score of ‘”duffers” and “lumpers” still active in the capital, concluding: “This trade is becoming now almost entirely a country trade.”

Meet the last of the Cornish packmen after the jump .

What surprises me, given all the above, is that a handful of packmen lived on in the more remote areas of the country as much as seven decades later. They kept trudging along long after the threepenny bus had wiped them out in London and the railway had reached almost every English settlement of any size—for the most part because, even as late as the middle 1920s, there were still places where the roads were more like paths and the hills sufficiently hazardous to be an obstacle to motor vehicles. Here the remnants of the breed survived, like dinosaurs in some forgotten world. They did so mostly on the Celtic fringe: in the Highlands of Scotland, the hills of mid-Wales, and in the furthest reaches of Cornwall. It was in the last of these, sometime around 1926, and somewhere south of King Arthur’s fortress at Tintagel , that H.V. Morton encountered the man we might reasonably assume to have been the last of the Cornish packmen.

I should pause here for a moment to introduce Morton, who is not often remembered now. He had fought in the Great War, in the heat and dust of Palestine, where he contracted a painful illness and assumed he was about to die. Afflicted by homesickness, Morton “solemnly cursed every moment I had spent wandering foolishly about the world… I was humiliated, mourning there above Jerusalem, to realize how little I knew about England. I was ashamed to think that I had wandered so far and so often over the world neglecting those lovely things near at home… and I took a vow that if the pain in my neck did not end forever in the windy hills of Palestine, I would go home in search of England.”

It was in fulfillment of that vow that Morton, some years later, found himself “bowling along” a country lane west of the Lizard, in the most southerly part of Cornwall. Although he did not know it, he was traveling at pretty much the last moment it was possible to tour the country and confidently greet strangers because “a stranger… was to them a novelty.” And in truth, Morton was also a determined nostalgist, who had deliberately followed a route that took him through all the most beautiful parts of the country, and avoided all the factory towns. Nonetheless, his wistful and often funny evocation of a vanishing country remains readable, and we can be glad that his road took him through the lanes south of St Just , for we have no better account of the traveling packman in his final days than his:

“This established contact,” Morton noted, and the two men sat by the side of the road, shared a pipe of tobacco, and talked.

But for all his years and his burden, Morton’s old man remained resilient:

This was the Jazz Age—Morton published his account in 1927—and the packman displayed ‘a smirk of distaste’ when invited to display the newest article in his pack: “clippers to crop shingled heads and many kinds of slides to hold back bobbed hair.”

“We fell to talking,” the account concludes, “of the merits of the packman’s profession.” Like all professions, it had its secrets—but the peddler’s view of its most vital skill of all took Morton by surprise. “Ef you wants to make money at this game,” the packman warned,

Envoi

Sources

Anon. The London Guide, and Stranger’s Safeguard Against the Cheats, Swindlers, and Pickpockets That Abound Within the Bills of Mortality… London: J. Bumpus, 1818; John Badcock. A Living Picture of London, for 1828, and Stranger’s Guide… , by Jon Bee Esq . London: W. Clarke, 1828; Rita Barton (ed). Life in Cornwall in the Mid Nineteenth Century: being extracts from ’The West Briton’ Newspaper in the Two Decades from 1835 to 1854 . Truro: Barton, 1971; John Chartres et al (eds). Chapters From the Agrarian History of England and Wales . Cambridge, 4 volumes: CUP, 1990; Laurence Fontaine, History of Pedlars in Europe . Durham: Duke University Press, 1996; Michael Freeman & Derek Aldcroft (eds). Transport in Victorian Britain . Manchester: MUP, 1988; David Hey. Packmen, Carriers and Packhorse Roads: Trade and Communication in North Derbyshire and South Yorkshire . Leicester: Leicester University Press, 1980; Roger Leitch. ‘”Here chapman billies tak their stand.” A pilot study of Scottish chapmen, packmen and pedlars.’ Proceedings of the Scottish Society of Antiquarians 120 (1990); Henry Mayhew. London Labour and the London Poor; A Cyclopedia of the Conditions and Earnings of Those That Will Work, Those That Cannot Work, and Those That Will Not Work . Privately published, 4 volumes: London 1851. H.V. Morton. In Search of England . London: The Folio Society, 2002; Margaret Spufford, The Great Reclothing of Rural England – Petty Chapmen & Their Wares in the Seventeenth Century . London: Hambledon, 1984.

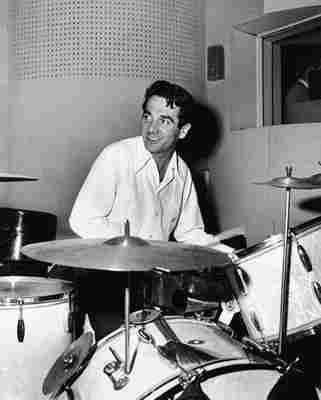

Gene Krupa: a Drummer with Star Power

When I was 7, my parents gave my brother a drum set. My brother was 14, and in my eyes he was a god; the drums he beat unmercifully in our living room added immeasurably to his aura. Made by Slingerland, they had a faux mother-of-pearl finish that caught the light in a way that suggested nothing short of magic.

A big part of this magic was that my brother’s drums—a snare, a big bass, two tom-toms (drums without snares), a high-hat (two cymbals brought together by a foot pedal), and two or three other cymbals—were exactly like those used by the great Gene Krupa. A drummer who had risen to fame with the Benny Goodman band, Krupa was to swing-era percussion what Gary Cooper and Humphrey Bogart were to movies of the day.

“Krupa was the first star drummer, the percussionist who transformed the drums from merely time-keeping to a prominent role as a solo instrument,” says John Edward Hasse, curator of American music at the Smithsonian Institution. Great drummers, including Buddy Rich and Max Roach, would follow his lead, but Krupa was the pioneer who gave percussionists the chance to take center stage. The drum set that inspired my brother now resides in the collections of the Smithsonian National Museum of American History.

Eugene Bertram Krupa was born in Chicago in 1909 andbegan playing drums professionally in the mid-1920s; he was soon working with such greats as bandleaders Eddie Condon and Glenn Miller, cornetist Bix Beiderbecke and saxophonist Coleman Hawkins. After he joined the Goodman band in 1934, Krupa—with his musicianship and good looks—became a major attraction. He was also a member of the Benny Goodman Quartet, with Teddy Wilson on piano, Lionel Hampton on vibraphone, and Goodman on clarinet. The quartet was one of the first integrated jazz groups, and certainly the most famous.

At a groundbreaking Benny Goodman concert in Carnegie Hall on January 16, 1938, Krupa’s sensational driving beat behind “Sing Sing Sing”—and his reprise of the number in the movie Hollywood Hotel —defined him as the very model of a modern drummer. According to Kennith Kimery, executive producer of the Smithsonian Jazz Masterworks Orchestra, Krupa’s fame had an unhappy consequence. “Krupa insisted on having drums in the forefront of the band. Benny Goodman wanted the audience’s focus to be on him,” Kimery says. “With certain numbers, Gene stole Benny’s thunder; in the end that cost him his job.” After leaving Goodman, Krupa formed his own band and became a frequent performer on television. He died in 1973 at age 64.

Around the time he left the Goodman orchestra in 1938, Krupa picked up a new set of Slingerland drums at the Fred Walker Instrument Company in Baltimore, Maryland, leaving his old instruments—emblazoned with his initials as well as those of Benny Goodman—at the company. In 1940, Walker customer Donald Hay, who played drums with a local swing band, bought the set. From 1944 to 1946, Hay served in the Navy, much of that time aboard the destroyer USS Wallace Lind , where he played drums with the ship’s band.

“After he got out of the Navy, he kept the drums in the basement and played along to big-band shows on the radio,” Leslie Schinella, the youngest of Hay’s three children, told me. “He had an Esso station and worked very long hours, so we heard him play mostly on Sundays.”

Hay died in September 2009 at 89. A hospice worker, Jennifer Betts, who had taken care of him, was the daughter of Keter Betts, singer Ella Fitzgerald’s bass player; Jennifer knew someone at the Smithsonian, and Schinella and her siblings agreed to donate their father’s drums to the Institution. “If a dealer had bought [them],” Schinella says, “we’d never have known where they went. But at the Smithsonian, they would be seen by a lot of people.”

When curator Hasse learned of the proposed gift, he and Kimery drove to Catonsville, Maryland, to verify their provenance. “The drums were the right vintage,” Kimery says. “They had calfskin heads, not modern synthetics; the tom-tom was on a tripod stand of the kind that isn’t used anymore. And of course there were the initials.”

At the Smithsonian, the Krupa drums will join a set used by Buddy Rich. Since the two masters were friendly competitors for the unofficial title of Crown Prince of Percussion, it’s a fitting reunion. Drum roll, please...

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions .

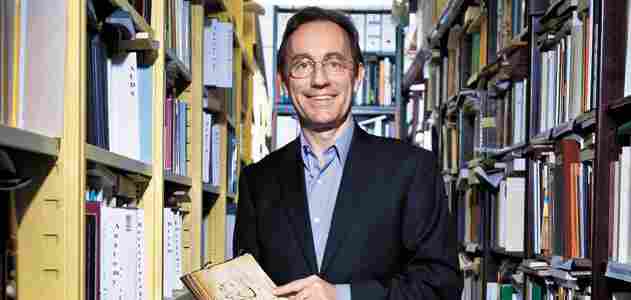

What Secrets Do Ancient Medical Texts Hold?

In 2002, Alain Touwaide came across an article about the discovery, some years before, of a medical kit salvaged from a 2,000-year-old shipwreck off the coast of Tuscany. Divers had brought up a copper bleeding cup, a surgical hook, a mortar, vials and tin containers. Miraculously, inside one of the tins, still dry and intact, were several tablets, gray-green in color and about the size of a quarter.

Touwaide, a science historian in the botany department at the National Museum of Natural History, recognized that the tablets were the only known samples of medicine preserved since antiquity. “I was going to do everything I could to get them,” he says.

Touwaide, 57, has devoted his career to unearthing lost knowledge. He is proficient in 12 languages, including ancient Greek, and he scours the globe searching for millennia-old medical manuscripts. Within their pages are detailed accounts and illustrations of remedies derived from plants and herbs.

After 18 months of negotiations, Touwaide obtained two samples of the 2,000-year-old tablets from Italy’s Department of Antiquities. He then recruited Robert Fleischer, head geneticist at the Smithsonian’s Center for Conservation and Evolutionary Genetics, to identify plant components in the pills. Fleischer was skeptical at first, figuring that the plants’ DNA was long degraded. “But once I saw plant fibers and little bits of ground-up plant material in close-up images of the tablets, I started to think maybe these really are well preserved,” he says.

Over the past seven years, Fleischer has painstakingly extracted DNA from the samples and compared it with DNA in GenBank, a genetic database maintained by the National Institutes of Health. He has found traces of carrot, parsley, alfalfa, celery, wild onion, radish, yarrow, hibiscus and sunflower (though he suspects the sunflower, which botanists consider a New World plant, is a modern contaminant). The ingredients were bound together by clay in the tablets.

Armed with Fleisher’s DNA results, Touwaide cross-referenced them with mentions of the plants in early Greek texts including the Hippocratic Collection —a series loosely attributed to Hippocrates, the father of Western medicine. Touwaide found that most of the tablets’ ingredients had been used to treat gastrointestinal disorders, which were common among sailors. Afflicted seafarers, Touwaide speculates, might have diluted the tablets in wine, vinegar or water to ingest them.

This latest research will be added to the holdings of the Institute for the Preservation of Medical Traditions—a nonprofit organization founded by Touwaide and his wife and colleague, Emanuela Appetiti, a cultural anthropologist.

“The knowledge to do what I’m doing is disappearing,” says Touwaide, surrounded by his 15,000 volumes of manuscripts and reference books, collectively named Historia Plantarum (“History of Plants”). With manuscripts deteriorating and fewer students learning ancient Greek and Latin, he feels a sense of urgency to extract as much information as possible from the ancient texts. He says they tell stories about the lives of ancient physicians and trade routes and contain even such esoterica as an ancient system for describing colors.

“This is important work,” says Fleischer. “He is trying to tie all this together to get a broader picture of how people in ancient cultures healed themselves with plant products.”

Post a Comment