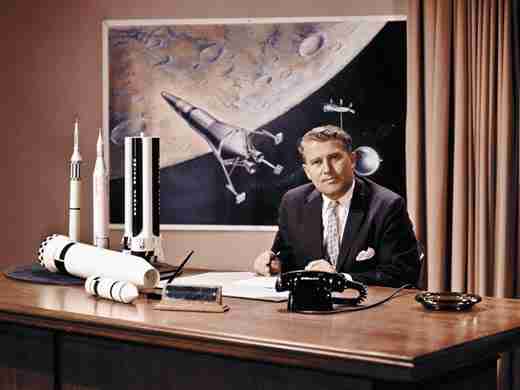

Wernher von Braun’s V-2 Rocket

In 1960, Columbia Pictures released a movie about NASA rocket scientist Wernher von Braun called I Aim at the Stars . Comedian Mort Sahl suggested a subtitle: But Sometimes I Hit London .

Von Braun, born in Wirsitz, Germany, in 1912, had been interested in the nascent science of rocketry since his teen years. In 1928, while he was in high school, he joined an organization of fellow enthusiasts called Verein für Raumschiffahrt (Society for Space Travel), which conducted experiments with liquid fuel rockets.

By the time Germany was at war for the second time in a generation, von Braun had become a member of the Nazi Party and was the technical chief of the rocket-development facility at Peenemünde on the Baltic Coast. There he oversaw the design of the V-2, the first long-range ballistic missile developed for warfare.

The “V” in V-2 stood for Vergeltungswaffe (vengeance weapon). Traveling at 3,500 miles per hour and packing a 2,200-pound warhead, the missile had a range of 200 miles. The German high command hoped the weapon would strike terror in the British and weaken their resolve. But though the successful first test flight of the rocket took place in October 1942, operational combat firings—more than 3,000 in all—didn’t begin until September 1944, by which time the British people had already withstood four years of conventional bombing.

England wasn’t the only target. “There were actually more V-2 rockets fired at Belgium than at England,” says Michael Neufeld, curator of the V-2 on view at the National Air and Space Museum and author of Von Braun: Dreamer of Space, Engineer of War . “In fact, the single most destructive attack came when a V-2 fell on a cinema in Antwerp, killing 561 moviegoers.”

The Air and Space Museum’s V-2 was assembled from parts of several actual rockets. Looking up at it is not unlike looking up at a skeleton of a Tyrannosaurus rex: each is a genuine artifact representing the most highly evolved menaces of their eras.

When the war ended in 1945, von Braun understood that both the United States and the Soviet Union had a powerful desire to obtain the knowledge he and his fellow scientists had acquired in developing the V-2. Von Braun and most of his Peenemünde colleagues surrendered to the U.S. military; he would eventually become director of NASA’s Marshall Space Flight Center in Huntsville, Alabama. There he helped design the Saturn V (in this case, the V stood for the Roman numeral five, not vengeance), the rocket that launched U.S. astronauts toward the moon.

During the war the Nazi regime transferred thousands of prisoners to the Mittelbau-Dora Concentration Camp to help build the V-2 factory and assemble the rockets. At least 10,000 died from illness, beatings or starvation. This grim knowledge was left out of von Braun biographies authorized by the U.S. Army and NASA. “The media went along,” says Neufeld, “because they didn’t want to undercut U.S. competition with the Soviet Union.” Von Braun always denied any direct role in prisoner abuses and claimed he’d have been shot if he’d objected to those he witnessed. But some survivors testified to his active involvement.

For many years the V-2 exhibit omitted any mention of the workers who perished. But in 1990, Neufeld’s colleague David DeVorkin created a whole new exhibit, including photographs and text, to tell the complete story.

The assembled rocket wears the black-and-white paint used on test missiles at Peenemünde instead of the camouflage colors used when the V-2 was deployed on mobile launchers. Museum officials in the 1970s wanted to underscore the rocket’s place in the history of space exploration and de-emphasize its role as a Nazi weapon.

Neufeld says that contrary to popular belief, the V-2 was more effective psychologically—no one heard them coming—than physically. “Because the guidance system wasn’t accurate, many [rockets] fell into the sea or on open countryside....In the end, more people died building the V-2 rockets than were killed by them.”

For all its political complexities, the V-2 remains historic, Neufeld says, “because, even though it was an almost total failure as a military weapon, it represents the beginning of space exploration and the dawn of the intercontinental ballistic missile.”

Owen Edwards is a freelance writer and author of the book Elegant Solutions .

Q and A with Bill Moggridge

This past November, Bill Moggridge , director of the Cooper-Hewitt, National Design Museum, received the 2010 Prince Philip Designers Prize—Britain’s most prestigious design award—for his lifetime contribution to the field. He spoke with the magazine’s Megan Gambino.

What is the biggest misconception about design? Many people think of “design heroes”—gifted people who strive only to create a beautiful project. Design is so much broader than that. It’s about solving problems.

In 1981, you designed the first laptop computer, the GRiD Compass, years before companies even began marketing desktop computers. What prompted you to do that? The impetus came from John Ellenby, an entrepreneurial engineer who had been working at Xerox PARC [Palo Alto Research Center] and founded GRiD Systems Corporation. He was talking to someone in the White House—someone with a top-secret job—whose computer was larger than his desk. This person said that what he really needed in order to do his job effectively was the same computing power encased in something that would fit in half his briefcase. And that became our guiding principle.

You specialize in “interaction design.” It’s the equivalent of physical design, but applied to the digital and virtual world. Back in 1981, I brought my laptop home, the first prototype I had the chance to use myself. For the first five minutes I was still proud of all the work I had been doing for a year and a half, thinking how valuable it was that I had created the physical form, with a nice looking display that folded over the keyboard. But soon I felt myself being sucked down into the virtual realm, concerned only with how I interacted with the software, and forgetting the existence of the physical object. That’s when I realized the significance of human-computer interaction.

Will the laptop survive in the 21st century? I think it will last forever. It’s a form that is very practical: a large display that’s the right distance from your eyes and an input setup—a keyboard plus a track pad or whatever it might be—right in front of you. And, it is very portable. We will continue to see new devices like the iPad, and there has been a lot of work on versions of computers with handwriting and voice inputs, so that all you need is the display. Some people will use that instead of their laptop. But I think these trends will exist in parallel with one another. I can’t see the laptop ever being completely replaced.

What object has the best design? If I think of very simple designs, I love something as uncomplicated as a paper clip, because it is such a neat way of solving a problem with very little material. If I think about something more sensuous, I’ve always been interested in the perfect spoon. It is delectable in a multisensory way: the appearance, the balance and feeling as you pick it up off the table, then the sensation as it touches your lips and you taste the contents.

I have heard that you want every child to have some exposure to design by age 12. How come? The ambition is to allow every kid to have some experience of design before they are 12 and the opportunity to study it in high school if they wish. That does happen in some other countries, but, at the moment, design is only included in specialist schools in the U.S. Design is an excellent bridge between the sciences and the arts, with designers developing both talents. They want to be problem solvers but they want to do it in some way that includes aesthetics, and the subjective values inherent in the arts. Design is a very powerful tool for young people to understand that they can learn by doing as well as learning by listening and trying to remember.

You once said in an interview that you learned the hard way to embrace failure as a faster path toward success. The willingness to embrace failure should be part of the design process, even if some design teams find that difficult to get used to. A lot of people will say, “Let’s wait until we get the prototype perfect before we actually show it to anybody.” The best way to achieve a result is to take the biggest risk as early as you possibly can, make a mistake and then go on and do it a second or a third time. You show it to people and try it out, let it fail and advance much more quickly.

George Ault’s World

The black barn in George Ault’s painting January Full Moon is a simple structure, bound by simple lines. Yet its angular bones give it a commanding presence. The barn stands at attention, its walls planted in moonlit snow and its peak nosing toward a deep blue sky. It is bold and brawny, and as Yale University art history professor Alexander Nemerov puts it, a barn with a capital “B,” the Barn of all barns.

A little-known American artist, George Ault had the ability in his painting to take specific locations in Woodstock, New York, where he lived from 1937 until his death in 1948, and make them seem universal. Nemerov says that places like Rick’s Barn, which Ault passed on walks with his wife, Louise, and Russell’s Corners, a lonely intersection just outside of town, held some “mystical power” to the artist. He fixated on them—painting Russell’s Corners five times in the 1940s, in different seasons and times of day—as if they contained some universal truth that would be revealed if he and the viewers of his paintings meditated on them long enough.

After fastidiously studying his scenes, Ault would retreat to a tidy studio to paint. As his 1946 self-portrait The Artist at Work shows, he worked with the elbow of his painting arm resting in the cup of his other hand, which balanced on his crossed legs. He was methodical and meticulous, often considered part of the post-World War I Precisionism movement. With his hand steadied, he could be sure that every plane, clapboard and telephone wire was just so. “There’s always this sense of shaping, ordering, structuring as if his life depended on it,” says Nemerov.

When you take into account Ault’s tumultuous life, perhaps it did. After attending the University College School, the Slade School of Fine Art and St. John’s Wood Art School, all in London, in the early 1900s, the Cleveland native returned to the United States where he suffered a string of personal tragedies. In 1915, one of his brothers committed suicide. In 1920, his mother died in a mental hospital. And in 1929, his father died. The stock market crash dealt a hard blow to his family’s fortune, and his two other brothers took their lives soon after. Grieving his losses, the artist left Manhattan with Louise, whom he married in 1941, for Woodstock, where he lived until December 1948, when he too committed suicide, drowning in a stream near his house. As Louise once said, Ault’s art was an attempt to make “order out of chaos.”

Ault did not get much recognition during his lifetime, in part because of his reclusiveness and hostile attitude toward potential buyers. But Louise worked tirelessly to promote her husband’s work after his death. Of Ault’s paintings of Woodstock from the 1940s, she once wrote, “I believed he had gone beyond himself.”

Nemerov, guest curator of the exhibition, “To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America,” at the Smithsonian American Art Museum through September 5, agrees. He sees Ault as having painted clear and calm scenes in a desperate attempt to control the muddled chaos not only in his personal life but also in the world at large, on the verge of World War II. Written on the gallery wall at the entrance to the exhibition is the statement, “If the world was uncertain, at least the slope of a barn roof was a sure thing.”

For the exhibition, the first major retrospective of Ault’s work in more than 20 years, Nemerov, a former pre-doctoral fellow and research assistant at the museum, selected nearly 20 paintings by Ault as well as ones by his contemporaries, including Edward Hopper, Andrew Wyeth and Charles Sheeler. Together, the paintings offer a much more fragile, brooding view of the 1940s than do other cultural icons of the decade, such as J. Howard Miller’s poster We Can Do It! (better known as Rosie the Riveter), Alfred Eisenstaedt’s photograph V-J Day in Times Square and Bing Crosby’s recording of “Accentuate the Positive.” Ault’s paintings are quiet and subdued—a road rising over a grassy knoll, a white farmhouse in the shadows of looming gray clouds, and a barren view of the Catskills in November. “It’s almost as though his paintings expect nine out of ten people to walk past them,” says Nemerov. “But, of course, they are counting everything on that tenth person to notice them.” For that tenth person, argues Nemerov, Ault’s works carry emotion despite their lack of human figures and storytelling. Nemerov calls the waterfall in Ault’s Brook in the Mountains , for example, “a form of crying without crying,” adding that “emotion—painting from the heart—must for him take a curious and displaced form to be real, to be authentic.”

In her foreword to Nemerov’s exhibition catalog To Make a World: George Ault and 1940s America , Elizabeth Broun, director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, emphasizes how art provides a means of understanding what individual people were thinking and feeling in a particular time, in Ault’s case during the 1940s. “Their specific thoughts and emotions died with them,” she says, “but this exhibition and book delve below the surface of forty-seven paintings to understand the deeper currents below, helping us recapture some long-forgotten insight.”

In the exhibition are all five of Ault’s paintings of Russell’s Corners, including Bright Light at Russell’s Corners , the third in the series, which is part of the American Art Museum’s permanent collection. Four of the scenes are set at night, and having them all in the same gallery allows the viewer to see how the black sky in each becomes more dominant as the series progresses. Buildings, trees and telephone poles are illuminated by a single streetlight in the first couple of depictions, whereas in the last, August Night at Russell’s Corners , which Ault painted in his final year of life, the darkness consumes all but two shadowed faces of barns and a small patch of road, as if Ault is losing the tight hold he once had on the world.

“I couldn’t blame people for thinking this is an unduly dark show,” says Nemerov. Perhaps for that reason, the art historian clings to the recurring streetlight in the Russell’s Corners series. “That light represents something that is about delivery, revelation and pleasure,” he says. He suggests that the light could have a religious connotation. Its radiating beams are reminiscent of the light in Sassetta’s 15th- century painting The Journey of the Magi , a reproduction of which Ault kept in his studio. But because the artist was not a religious man, Nemerov considers the light a symbol of the ecstasy and exhilaration of an artistic act, a burst of creativity. After all, out of Ault’s turmoil came one glaringly positive thing: an impressive body of art. Quite fittingly, Louise used a quotation from the German philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche to describe her husband. “Unless there be chaos within, no dancing star can be born.”

Post a Comment